Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

Text: Eri Ishida

Photo: Keisuke Fukamizu

2022.04.05

For all the modernity of the designs that dyer Takeshi Yamauchi creates using the stencil-dyeing technique called katazome, there’s something familiar and distinctly Japanese to them. Yet the craft that eighty-one-year-old(at the time of the interview) Yamauchi continues to practice daily at his workshop in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture is hard to fit in any box. It is deeply colored by memories of the six years he spent as a young man training under Keisuke Serizawa (1895–1984), a central figure in Japan’s folk art movement and a dyer recognized as a Living National Treasure.

Taught to “Make the Fabric Live.”

I don’t believe there are many people who continue to exist, decades after departing this world, not only through their great achievements but also as images etched so vividly into the memories of those who knew them that they still seem to be alive. I have visited the katazome artisan Takeshi Yamauchi a number of times in his studio in Hamamatsu, and every time I do, stories of his long-departed teacher, the dyer Keisuke Serizawa, fill our conversation. Yamauchi has been working independently for over fifty years, but the memories remain as fresh as ever and the stories more eloquent than those he tells about himself. Listening to him recount these episodes as if they took place only yesterday, I have come to believe that the dyeing work of Takeshi Yamauchi is the product of an ongoing dialogue with his teacher.

This teacher from whom Yamauchi has never fully detached himself was born in the city of Shizuoka and went on to be named a Living National Treasure in the field of “katae-zome,” a similar form of stencil dyeing. He was also a central member of the folk art movement led by the philosopher Soetsu Yanagi, who found beauty in the handmade objects used by ordinary people in their day-to-day lives and articulated the essence of folk art.

As a child, Serizawa had dreamed of becoming a painter, but his family circumstances forced him to give up this hope. Instead he pursued design, and in the course of this work he encountered and became deeply engaged with dyeing. In 1928, he attended a folk art exhibit held as part of an exposition at Ueno Park to mark the succession of the Showa Emperor to the throne, where he saw a display organized by Yanagi on bingata, the traditional Okinawan resist-dyeing method. Deeply impressed by the patterns, colors, and materials of the dyed fabrics, he decided to pursue the path of stencil dyeing in earnest. Up until this point the tasks of drawing designs and dyeing them onto fabric had typically been performed by different artisans, but by performing every step of the process himself, as was done in bingata dyeing, Serizawa was able to develop his own style. In contrast to the traditional patterns of bingata, his style was freer and looser, depicting motifs such as geometric patterns, characters, animals, and scenes from daily life. Later, when he was designated a Living National Treasure, this style of stencil dyeing was given the name “katae-zome,” which literally means “stenciled-picture dyeing.”

“As Seiichiro Shiratori [curator at the Serizawa Keisuke Art Museum] once said, ‘Serizawa hated promoting himself, and so it was only when he was designated a Living National Treasure at sixty-one that he became known throughout Japan, but unfortunately the public view of him was limited to his identity as a dyer. In truth, the phrase ‘master of katae-zome dyeing’ could never contain all of who he was. He was much more than that,’” Yamauchi told me. Indeed, the imposing label of Living National Treasure outshines the fact that Serizawa was a painter so gifted that Balthus and other Parisian artists praised his work; an accomplished designer who built his skills starting in high school; and a collector even his lifelong mentor Soetsu Yanagi acknowledged as having an eye for beauty superior to his own. Motivated equally by the admiration for craftsmanship that his upbringing in a family of kimono fabric and cotton goods wholesalers instilled in him at a young age, his early artistic inclinations, and the philosophy of the folk art movement, he established a studio in Tokyo’s Kamata district in 1955. Shortly after, Yamauchi joined the studio as an apprentice.

“But you see, I didn’t join because I admired Serizawa, like Samiro Yunoki [a senior apprentice of Serizawa’s]. My family was originally in the business of embroidery, and later dyeing, and many years earlier my father had worked as Serizawa’s assistant. He told me to go study under him for five or six years. That was right after I graduated high school, when I was eighteen,” Yamauchi said.

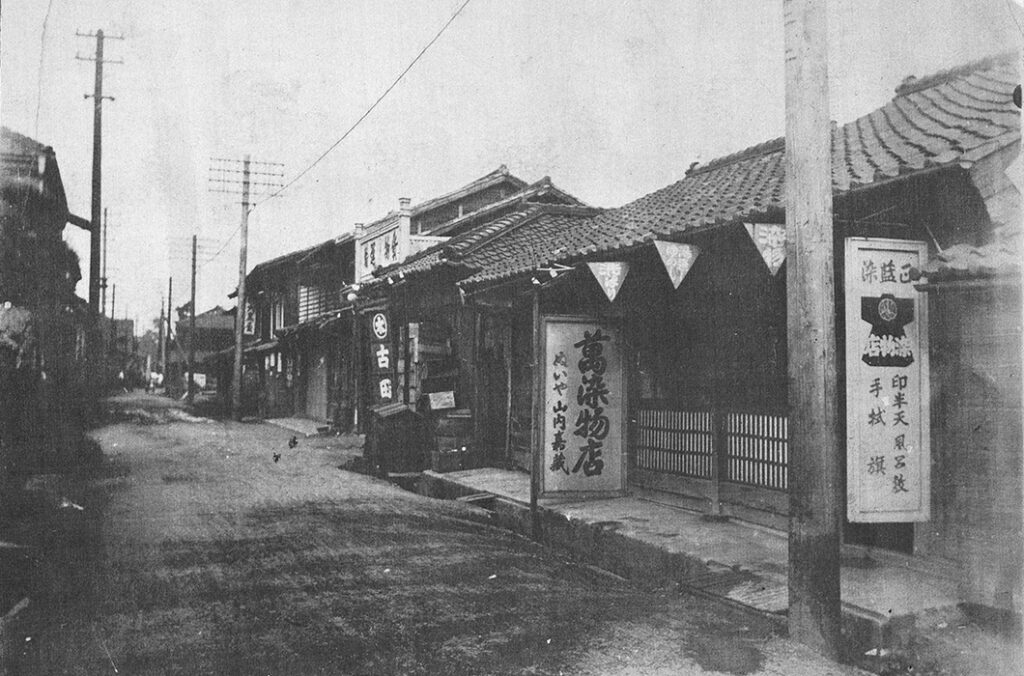

Enshu—the western area of Shizuoka Prefecture that includes Hamamatsu—had been an important cotton farming region since the Edo period. The type of textiles known as Enshu orimono began as a side business for the farmers that grew gromwell and indigo plants for dyeing, but it eventually developed into a major regional industry, of which Yamauchi’s family was one small part.

“In Hamamatsu alone there used to be three or four dyeing factories that each employed around three hundred people, along with countless little family-owned workshops like ours. The industrial high school I went to had an industrial chemistry department, but it might as well have been called the dyeing department. Although I was the only one of my siblings who decided to go into the family business, my father was a little worried about my future. Dyeing was already a declining industry at the time. Up until then, the merchants had all ordered work coats with the company crest on them from local dyers, but around that time they started ordering off-the-rack coats. I guess my father was right, because not one of those factories is left in the city today. I think he wanted me to pursue craftsmanship in a broader sense, even if I went into dyeing.”

Yamauchi both lived and worked at Serizawa’s studio. He was a useful employee, in part because he had excelled since high school at chemistry, foundational to dyeing. Nevertheless, working for Serizawa was not easy; as he himself wrote, even when the master had drawn a preparatory design, he would often alter it as he cut the stencils, or change the colors used on the same stencil according to his mood, so that his apprentices were constantly in a state of confusion.

“His shifting moods weren’t so bad, but what made him difficult to work for was that he never gave an ordinary answer. For example, say one of us was in his room and he held some item up and said, ‘That guy needs to take a look at this.’ If we left without realizing what he meant, we’d get a good scolding later. Once we got together to reminisce about him at the Serizawa Keisuke Art Museum, and it was nonstop hard luck stories. Even Yunoki had some tough times. When it came to putting together an exhibit, the master potter Shoji Hamada used to tell his apprentices, ‘I’m leaving it all up to you’ and not say another word, but Serizawa would say the same thing and then not leave a single thing up to us. For example, when he had an exhibit in 1976 at the Grand Palais in Paris, we ran through it over and over in Japan, only for him to change everything once we got there. But you see, he was implicitly teaching us that with katazome, things may look as if they’ve been decided, but in fact you can change them right up to the very end.”

The hard experiences of the old days eventually became funny stories. Yamauchi always speaks of Serizawa in this way, but behind these episodes lies a great affection for a teacher who “loved to have a good time with all of us and would do things like dress up in costumes for our Christmas parties.”

At the time the studio employed around thirteen apprentices who were divided into cloth-dyeing and paper-dyeing teams, the latter of which Yamauchi eventually led. Serizawa’s paper dyeing work had its origins in the covers he created for Mingei, a folk art magazine edited by Yanagi, and he later came to be known for his paper calendars, fans, and other consumer items. He also created individual works for the yearly Kokuten exhibits in Tokyo.

“Once, when I showed Serizawa something I had dyed, he said it was good. I thought it was odd that he’d complimented me, so I took a closer look and realized he was looking at the back side of the fabric. True, the back side does turn out more interesting than the front sometimes, but still. I felt like he’d seen through a mistake of mine, and I should have just kept my mouth shut, but instead I made some excuse. He said, ‘I have no interest in pieces that come out how you planned. If you don’t mess up, there’s nothing interesting to see.’ At the time I felt like he’d been unnecessarily harsh, but a long time afterwards, those words became a source of security. He said many things that even today I feel I need more time to truly understand.”

Make a drawing, cut a paper stencil, make a resist paste, apply the paste. Once it dries, paint the dye on with a brush, then wash the fabric. The steps in katazome dyeing are the same as for bingata. “You can’t cut corners on a single step,” Yamauchi said as he began his usual process of making noren curtains. “Serizawa was a perfectionist himself, but I’m at least as bad as he was.”

His workshop is next to his home. Immediately inside the entrance is the washing station, and beyond that is the area where he applies pastes over the stencils, forming a mirror image that will resist the dyes. On clear, mild days, Yamauchi dyes in the garden. He goes to his workshop nearly every day, resting only occasionally when it rains. Nor can he dye on days, starting in November, when the hard, dry winds unique to this region are blowing. In order to accomplish by himself tasks that normally require several people, his workshop is full of personal innovations, like a system of posts and strings that allows him to stretch and tighten strips of fabric by hand. He never stops moving. As I looked at the faded photograph of his teacher hanging on the wall, I felt as if he was still watching over every detail of Yamauchi’s work.

“About six months before Serizawa died, I visited his studio in Kamata and he said to me, ‘Not a day goes by that I don’t think of you.’ I hadn’t been expecting that. I asked him if something was wrong, because at the time his words made no sense to me. But if he said the same thing to me today, I would answer, ‘Likewise.’ I wonder how he’d react to that.” Yamauchi paused for a moment in applying paste, then began again as he continued.

“I’ve been able to work as a dyer my entire life because he laid the groundwork. What I mean is, he created demand for dyed goods through the strength of his designs. Take these noren. It used to be only merchants who bought them. Ordinary households had no use for them. But Serizawa’s designs created a new genre in the market. The same goes for fans. The things I want to make are everyday items. Even when I work very hard and create something good, it would never do for me to insist to hold onto it. When it’s gone, I can just make another one.”

Yamauchi uses traditional methods that require several days to make a single item, but since his time with Serizawa he has pared away many elements so that his designs are now extremely minimal. His cheerful, easygoing personality is evident in the fact that he leaves no clues in his finished pieces of the extensive labor required to make them. About half his work still consists of commissions on a particular theme, often to commemorate an occasion. For example, his alphabet series began when Sori Yanagi, Soetsu Yanagi’s eldest son and a renowned industrial designer, visited the workshop and delighted in a noren with his initial “Y” on it that Yamauchi had created for him. Even when fulfilling orders, however, he often changes the design or color as he goes, according to his mood, frequently straying from the original commission. This, too, is an inheritance from his teacher.

“There’s nothing special about creating a piece solely based on my own ideas. That’s because it never goes beyond the bounds of my imagination. I’m more suited to situations where I’m given a theme and have to try to come up with the best thing I can within that framework. A long time ago, Serizawa wrote a piece for the magazine Mingei called ‘On Design.’ It was a very good piece. ‘When you dye, don’t just put pictures on the fabric. Make the fabric live,’ he wrote. He meant that we should value the materials, think about how the piece will be used, and then and only then apply the design and the colors. I’d always liked to make things, but I didn’t like drawing much. When I was with Serizawa, that surfaced and was beaten down. You couldn’t do the work if you didn’t draw. Yanagi taught us that ‘In the past, uneducated and illiterate people made wonderful things.’ I wanted to believe his words, so I decided to continue. But when I think back on it now, I realize that worrying about it was a big mistake. When I was young, I thought I had to make something unique, different from everyone else. I assumed the pieces I made were my own, but in the end, it was the era that shaped what I made. I’ve come to feel that way. It’s all about the coming generation, always. It’s up to them to keep the art alive.”(Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 2)

Takeshi Yamauchi’s Katazome Noren are available for purchase on our official web store.

Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

Sol LeWitt: Open Structure

2026.02.16

Artisan

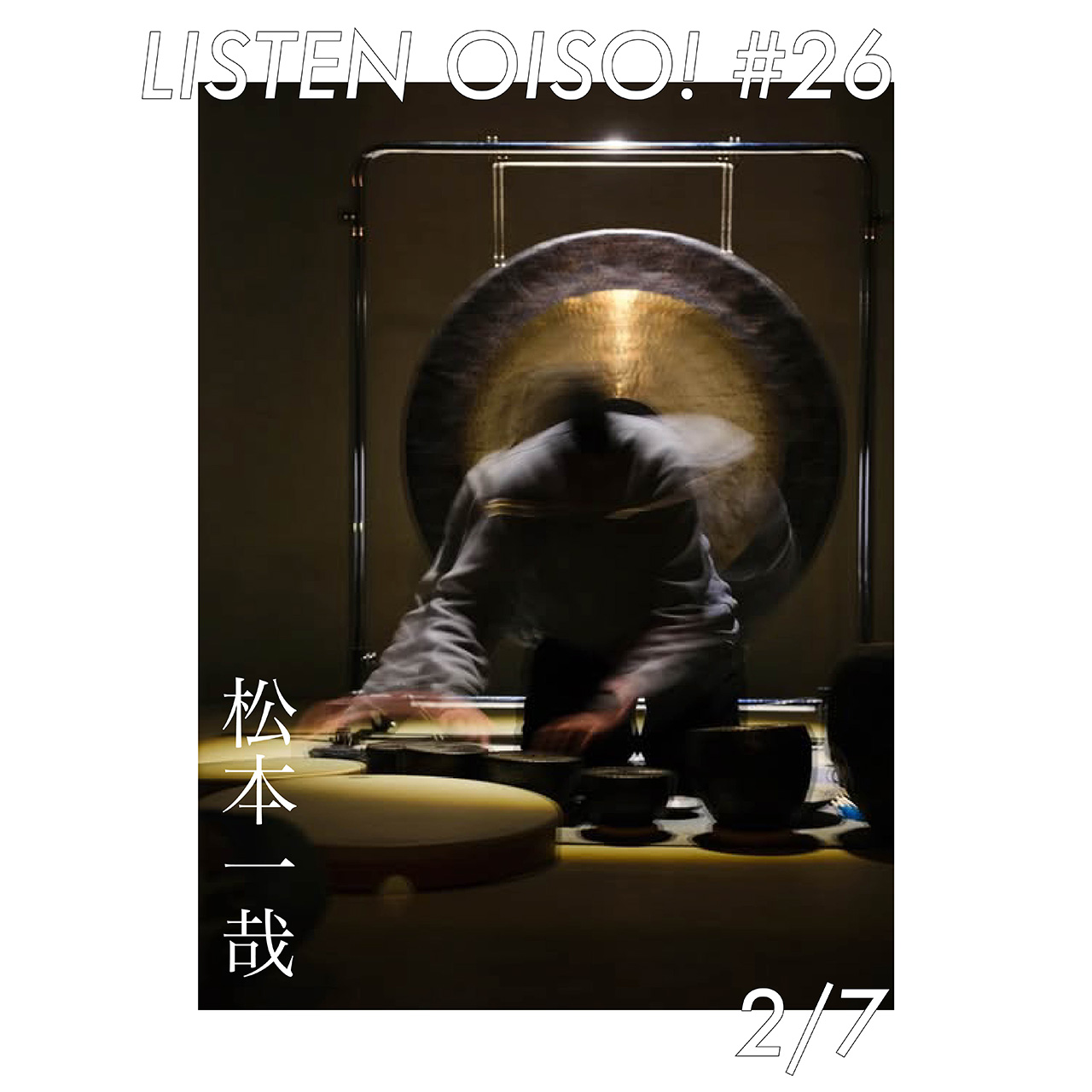

LISTEN OISO! #26

Daysuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsuda, and Kazuya Matsumoto

2026.01.26

Artisan

Lingering Memory / Michiko Van de Velde

2025.11.12

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025