Artisan

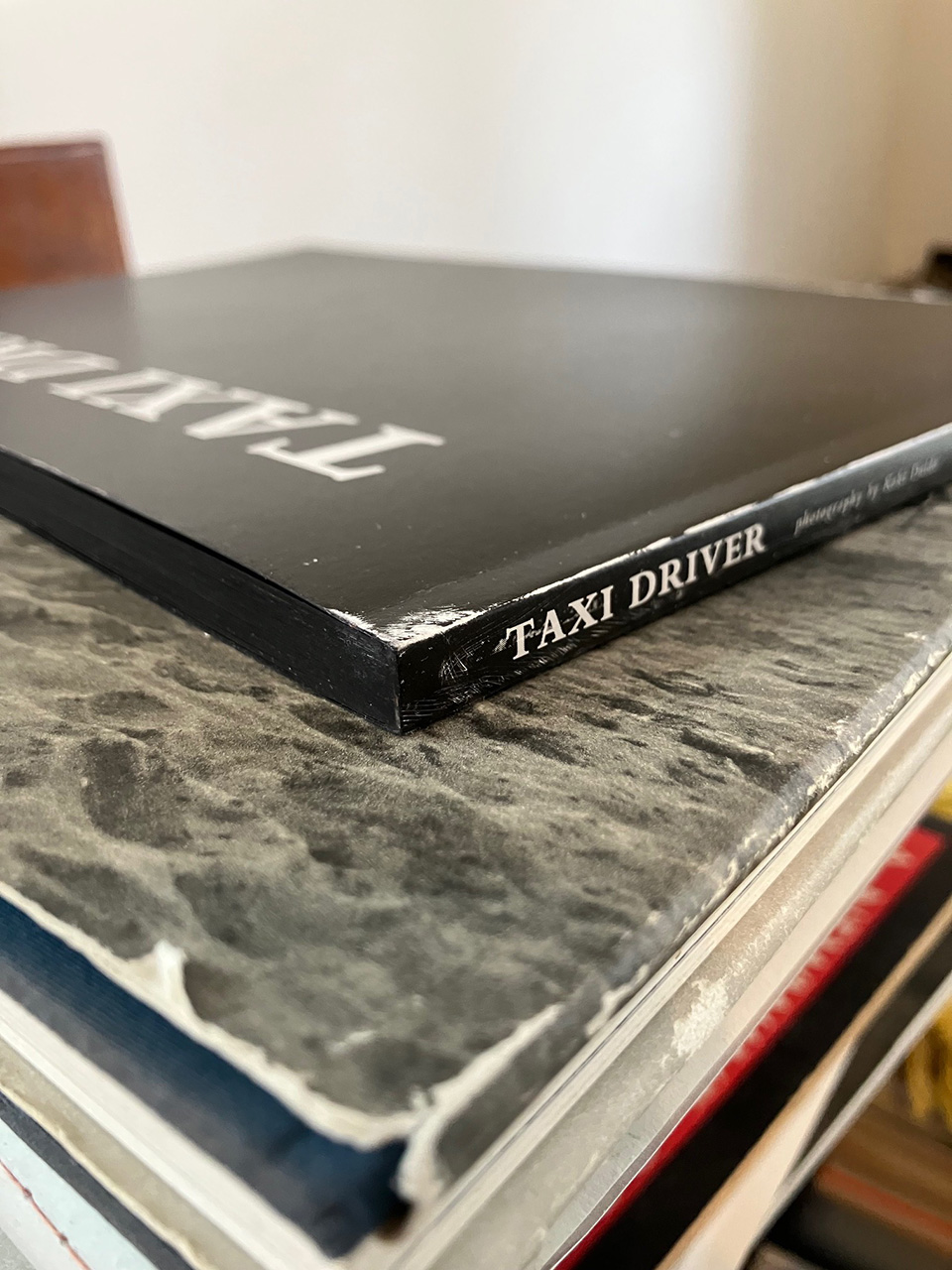

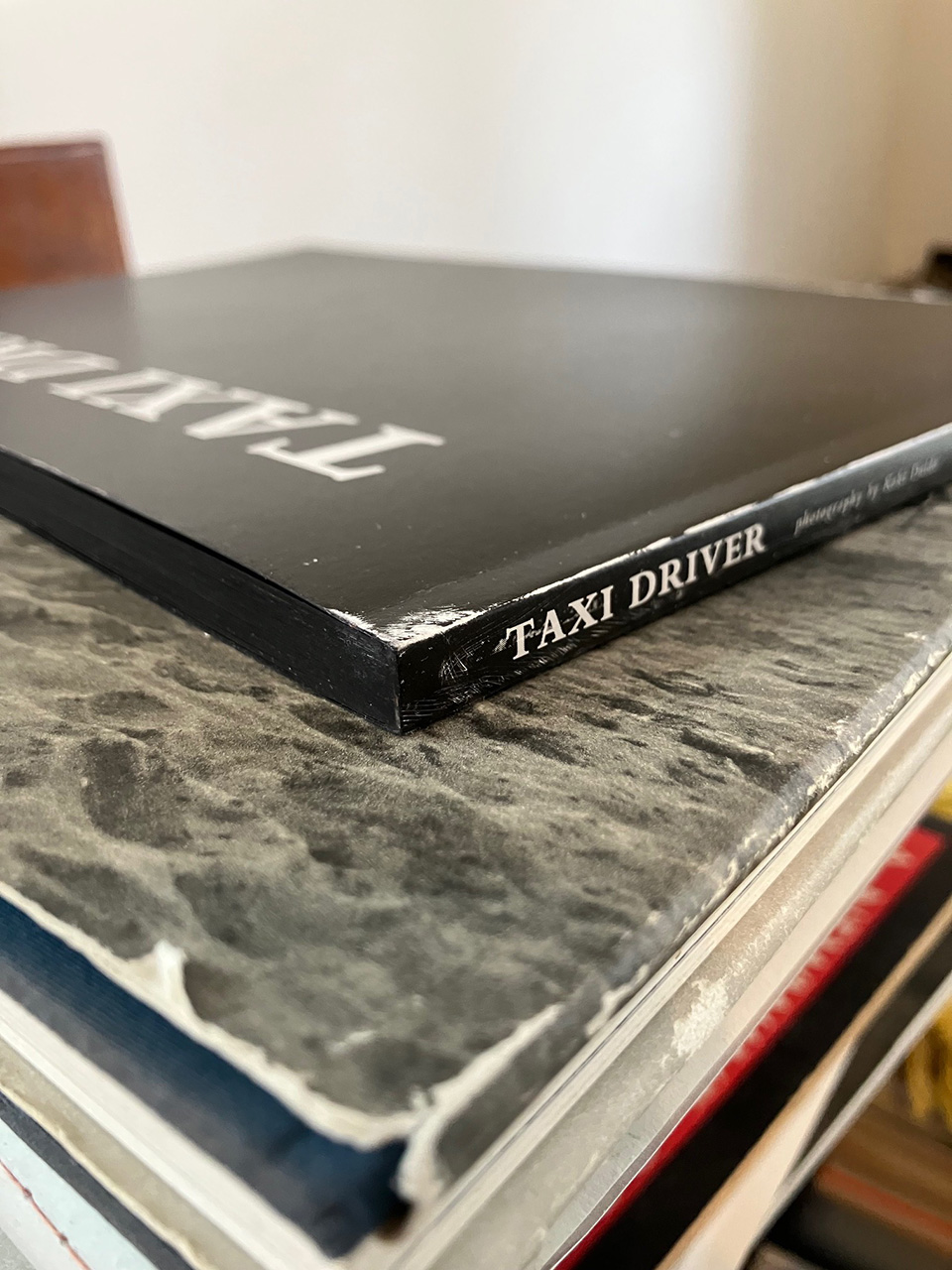

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

Text: Chisa Sato

Photos: Yoichi Nagano

2022.04.26

Ako dantsu rugs were developed by Naka Kojima in the early Meiji era. Though the original techniques were at one point nearly lost, a small handful of weavers in the seaside city of Ako passed them on. Then one woman fell in love with a century-old rug. She learned to weave herself and began to restore antique Ako rugs, helping to revive an almost forgotten Japanese handicraft.

Nearly two centuries ago, an encounter with a rug changed one woman’s life.Today, her legacy of handweaving lives on.

As the flying carpet of the One Thousand and One Nights illustrates, rugs have evoked a certain mystery and romance throughout the ages. Perhaps this is because they are imbued with feeling by the human hands that weave them, telling through their patterns the rich stories of everyday life that travel to us across centuries and national borders.

I sat in the dim interior of a traditional wooden townhouse as rugs were unrolled before me one after another. The smell of age wafted upward from them, captivating me with the sensation of having suddenly traveled through time to a distant land. This was my introduction to Ako dantsu rugs. I gazed at one with a bold zigzag pattern of swords and a gradation of blues reminiscent of sky and sea, set against a white background, feeling as if I were in an oasis city on the Silk Road. I suddenly recalled the Hayao Miyazaki animated film Nausica of the Valley of the Wind, whose fantasy-world setting is said to be based on central Asia.

“This design is called Amiriken. It depicts a sword that slays evil and a net that captures happiness, and it is one of the most well-known Ako rug designs,” explained Rie Sakagami, in a calm, unfaltering voice. A weaver herself, she also repairs and sells old rugs at her studio, Ako Dantsu Mutsuki. My unaccustomed ears mistook the word Amiriken for “American,” and I gazed down at the rugs as curiously as someone from an earlier age seeing an imported carpet for the first time. How, I wondered, had these exotic floor coverings with their unique designs emerged here in Japan, where tatami and other types of flooring were traditionally left bare?

Together with Sakai dantsu rugs from Osaka and Nabeshima dantsu rugs from Saga, Ako dantsu rugs number among Japan’s “big three” rug styles (dantsu means “carpet,” but these are often much smaller than that term would suggest). Woven in the city of Ako in Hyogo Prefecture, these rugs reached their peak of popularity between the Meiji and early Showa periods. They are made from cotton, as opposed to the more typical wool or silk. Prized by tea masters and other members of the Kyoto elite for their elaborate craftsmanship and colorful patterns, they were brought out for special occasions such as tea ceremonies and the annual Gion Matsuri festivities. They were also used in the imperial train that carried the emperor and empress during the Meiji period, a fact that enhanced their reputation and fame. At the height of their production in 1912, the six workshops in Ako wove about 5,800 square meters of product, granting the rugs status as Ako’s signature handicraft.

However, production was suspended during World War II due to restrictions on cotton yarn. After the war, two workshops reopened, but they later declined under the assault of rapid economic growth. The number of rugs on the market eventually dwindled so dramatically that they were nicknamed “the phantom rugs of Ako.” In 1991, the last workshop closed. Fearing the techniques would be lost forever, the city government launched a series of lessons taught by Ako’s last weaver, Kirie Sakaguchi. Today, many of her students have opened workshops where they continue to weave the rugs.

Sakagami trained under one of these women before opening her own studio in Ako. Paying her a visit, I was soon led through the untold world of these rugs.

Ako has long been known as the home of the Forty-Seven Ronin, those leaderless samurai who famously avenged their dead lord. It is a beautiful city facing the Inland Sea, on the border western border of Hyogo, abutting Okayama. Favored by the bounty of the sea’s placid waters, Ako has flourished since ancient times thanks to its excellent natural port and salt-making industry. “Nature is abundant here, and there are few natural disasters, so Ako people are generally easygoing,” says Sakagami, who is originally from the city of Kobe. I had driven west from Himeji over a mountain pass to reach Ako. As I descended the far side, the landscape opened up magnificently, with the town lining the banks of the sparkling Chikusa River all the way down to the sea. It was like a quintessential, even nostalgic view of old Japan.

The techniques for making Ako rugs were developed in the early Meiji era by a woman named Naka Kojima. I wondered what she was like, this woman who decided to begin producing the sort of rugs which had previously only been imported. To find out more about the history of Ako rugs, I met with Kokoro Kiso, curator of the Ako City Museum of History. She told me that the only record of Kojima consists of a brief entry in a book called The History of Ako.

According to that document, Kojima was born in 1823 to a wealthy family and grew up loving to paint and make handicrafts. When she was nineteen, her family married her to Saburobyoe Takai and adopted him into the family to carry on the Naka name. Fortunately, it seems that he was a good husband. In Edo, he worked in the service of feudal lords purchasing artwork, while in Osaka he traded in imports. He was known as an excellent judge of art, which perhaps was why the Kojima family chose him as their heir.

On a trip with her husband to the city of Takamatsu, on the island of Shikoku, Kojima saw a type of Chinese rug called “banrekisen.” Greatly impressed by her first glimpse of a foreign rug, she made up her mind to learn to make them herself and go into production with her father and husband. She seems to have been gifted not only with outstanding aesthetic sense but also with a good head for business. She poured herself into making the rug, forgetting even to eat and sleep as she experimented with various techniques, such as using the wooden frame from a kotatsu table in place of a loom. At the age of twenty-six, she finally succeeded in weaving a ten-centimeter sample. However, she could not advance beyond that point. Hoping to find inspiration for her patterns in other types of rugs, she once again traveled with her husband to Shikoku, as well as to Kyushu and the Chugoku region. The trip yielded significant results, which formed the basis for her eventual success, at the age of fifty-one in 1874, in completing a rug the size of a typical tatami mat (about one meter wide by two meters long). She developed sales networks in Kyoto and Osaka, succeeding in her vision of creating a commercial product. A quarter century had passed since she first saw the banrekisen rug.

“The reason it took her so long to make a prototype was that she didn’t know how the rugs were made, and since neither the techniques nor the tools existed in Ako at the time, she had to reinvent the wheel,” Kiso told me. “There were also probably periods when she had to put aside her work, like when she was raising her children. That said, it was rare for a woman to travel so extensively during the Edo period. I imagine they were quite a progressive couple.”

In those days, it was unheard of for wealthy women to work yet Naka devoted her life to designing and producing Ako rugs. Her passionate devotion and extraordinary resourcefulness put Ako rugs on the path toward becoming a regional industry. Amidst the social and economic upheaval of the late Edo and early Meiji periods, it was extremely rare for a woman to lead the way in founding a new industry. Even within Japan’s broader history, it is a noteworthy accomplishment. But information about Kojima is as scarce as her contributions were vast, reminding me just how difficult it was for women to take on prominent public roles in her day.

At the same time, I was conscious of the powerful determination she must have maintained over many long years to develop the techniques and designs needed to make Ako rugs a full-fledged handicraft. That is precisely why they were of such high quality, and why their popularity grew as an emblem of a new era blending foreign and domestic styles. Her success in overcoming the societal restraints imposed on women as well as the limitations of her time refracts a small glimmer of hope down through history. Her example must be an encouragement to Sakagami, Kiso, and the many other women connected to her in one way or another over the years.

Just as Naka Kojima encountered banrekisen rugs by chance and was powerfully captivated by them, Sakagami learned about the rugs Kojima had developed through a twist of fate and dove headlong into their world. Eight years ago, she was on her way to the hot springs in Ako when she happened to stop at a gallery in Misaki and see an antique Ako rug for the first time.

“I fell in love with it instantly,” she told me. “I was amazed to learn not only that this style of rug had been developed in Japan, but that this daring, exotic pattern, unlike anything I’d ever seen before, had been woven a hundred years ago.”

Pulled in by the strange magnetism of the unknown, Sakagami had already decided to become an Ako rug weaver by the time she headed home from the hot spring. She was in her late twenties and unsure of her path forward, but had recently been feeling that she wanted to make a life as a craftsperson. She contacted the gallery’s owner, a weaver named Kazue Hashiba, who introduced her to a more experienced weaver named Setsuko Negoro. Sakagami became Negoro’s apprentice.

“Weaving rugs is fairly simple work. As long as you put in the time and keep patiently at the task, it will take shape. With crafts like pottery and glassblowing, success is determined by a few short minutes of creation, and that demands intense training. I think that for someone like me who entered the world of handicrafts without any experience, rugs were a better fit. In that sense, it was quite a rational decision,” she said, thinking back on a major turning-point in her life.

Sakagami had liked drawing and crafts since she was a child, and in university she was involved in set design for a theater troupe, but until learning to weave, she had never made crafts for a living. After graduating from a university in Tokyo, she took a job at a large apparel chain, working hard as part of the team that opened new stores. As soon as one new store was up and running, she would be transferred to a different location to repeat the process. “The work was rewarding, but I realized I couldn’t do it for my whole life,” she said. She hoped to eventually move to the shores of the Inland Sea, where she was from, and grow old doing creative work. That was her mindset when she discovered Ako rugs and found a path to which she could devote her passion. Her decisiveness and ability to put ideas into action were remarkable. She studied with Negoro for five years, then three years ago established her own studio. Sakagami is one of very few young people from outside of Ako to have taken up weaving Ako rugs.

The Ako Misaki district occupies the end of a cape once lined with rug workshops. While the men worked the salt fields, the women wove. Sky and sea meld in a gentle blue, resonating with the colors of the Ako rugs. Sakagami opened her studio here, she said, because “I wanted to look out on the same landscape as the weavers of a hundred years ago.”

She showed me the first rug that she ever wove. A reworking in new colors of the classic “Craggy Mountain” pattern, she said it took about a year to make, but the quality was so good I would never have judged it the work of a beginner. The rug gave off the lively pleasure of creation, as if she had been enjoying her work at the loom to the full.

Sakagami sat down at a huge handloom that took up most of the room and began to weave a rug. The sharp clacking of the comblike reed filled the workshop. Weaving is quite physical work. The hallmark of Ako rugs is a process called trimming, in which a pair of clippers with angled blades is used to clip the ends of the fibers, giving the patterns three-dimensional depth. Trimming the boundaries between colors makes the pattern stand out more, while trimming the background makes the surface smoother and softer. A final trimming further differentiates the pattern from the background. This technique, not used in Nabeshima or Sakai rugs, is largely responsible for the delicacy and vibrancy of the patterns on Ako rugs. The time required for trimming explains why weaving a single tatami-sized rug takes six months to a year.

Another distinguishing feature of Ako rugs is the use of tall horizontal looms, or takabata, rather than the vertical looms typically used to weave carpets. The loom design was most likely adapted from those used to weave kimono fabric. In addition, starched yarn is used for the warp and weft, giving the weave a unique tension and durability. These distinctive “inefficiencies” are evidence of the great pains Naka Kojima took in developing her method.

In addition to weaving new rugs, Sakagami restores old ones. She began this line of work as a side gig while she was training with Negoro, but she had always liked old things, and soon became completely absorbed. Because there are very few Ako rugs on the market today, antique dealers typically do not distinguish between Nabeshima, Ako, and Sakai rugs, instead handling them all as worthless old textiles.

“If we don’t buy up the old rugs and restore them, this wealth we have inherited from past weavers will be lost,” Sakagami told me. “That’s why I want to get as many of them as possible back in circulation after restoring them. That way, more people will be able to recognize Ako rugs, standards of quality will be established, and a market will develop. The rugs made during the peak of production are first rate in terms of dyeing, weaving, and design, and they were made using techniques that have been lost. My hope is that by bringing them back to life, they will enjoy many more years of daily use.”

Restoration involves much more than simple cleaning. Sakagami must have an image of the finished product in order to determine how to wash and fix a rug. She researches how they were originally woven and dyed, sometimes repairing tears or adding color. In winter, washing is a battle against bitter cold. Nevertheless, the 200 or so old rugs she has handled provide a wellspring of inspiration for her own weavings.

“In the course of restoring these old rugs and weaving my own, I’ve come to appreciate all the effort that Naka Kojima put into inventing these incredibly labor-intensive techniques, as well as the perseverance and passion of the weavers,” she said. “I’m especially drawn to the sharp geometrical patterns that are unique to Ako. How will my own rugs look in a hundred years? I’ve begun to take that kind of broad, long-range perspective.”

Through restoring and weaving rugs, Sakagami has retraced the creative path that led Naka Kojima to develop Ako rugs. Her body carries out the same work that was once done with such vitality by over a hundred weavers in Ako. Thus is the nature of weaving: it is shot through by the unbroken thread of female experience. Now Sakagami’s inquiring mind has turned toward revealing the unknown history of Ako rugs. What, exactly, were the banrekisen rugs that Naka Kojima saw? Who designed the numerous colorful patterns? The answers remain swathed in mystery. Sakagami searches for hints in Kyoto, where many Ako rugs are still in daily use, making it a prime location for collecting evidence and buying unusual old rugs that she discusses with Kiso. One might even say she shares the passion that inspired Naka Kojima to try weaving a banrekisen rug herself.

In Ako, on the shore of the Inland Sea, there was once a thriving industry of beautiful handmade rugs. Today, about twenty weavers have established workshops where every stage in the production of a rug is carried out by one set of hands. The process is unavoidably time-consuming, and the price is correspondingly high. The situation is different from when Ako rugs were an established industry.

Nevertheless, Sakagami has settled in Ako and begun to illuminate the story of these rugs, unearthing fine old examples and sharing the craft with other outsiders in an attempt to reclaim their former glory. Naka Kojima has taught her that there is value in resisting the trends of a world that rewards efficiency to instead perform time-consuming, inefficient labor—that deepening her understanding and devotion in this way will yield meaningful results.

“I want to learn more about the history of Ako rugs and record what I find in a book,” she said. And so her work continues, with the hope that Ako rugs will still be around in another hundred years. (Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 4)

Old Ako Dantsu Rugs restored by Rie Sakagami are available for purchase on our official web store.

Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

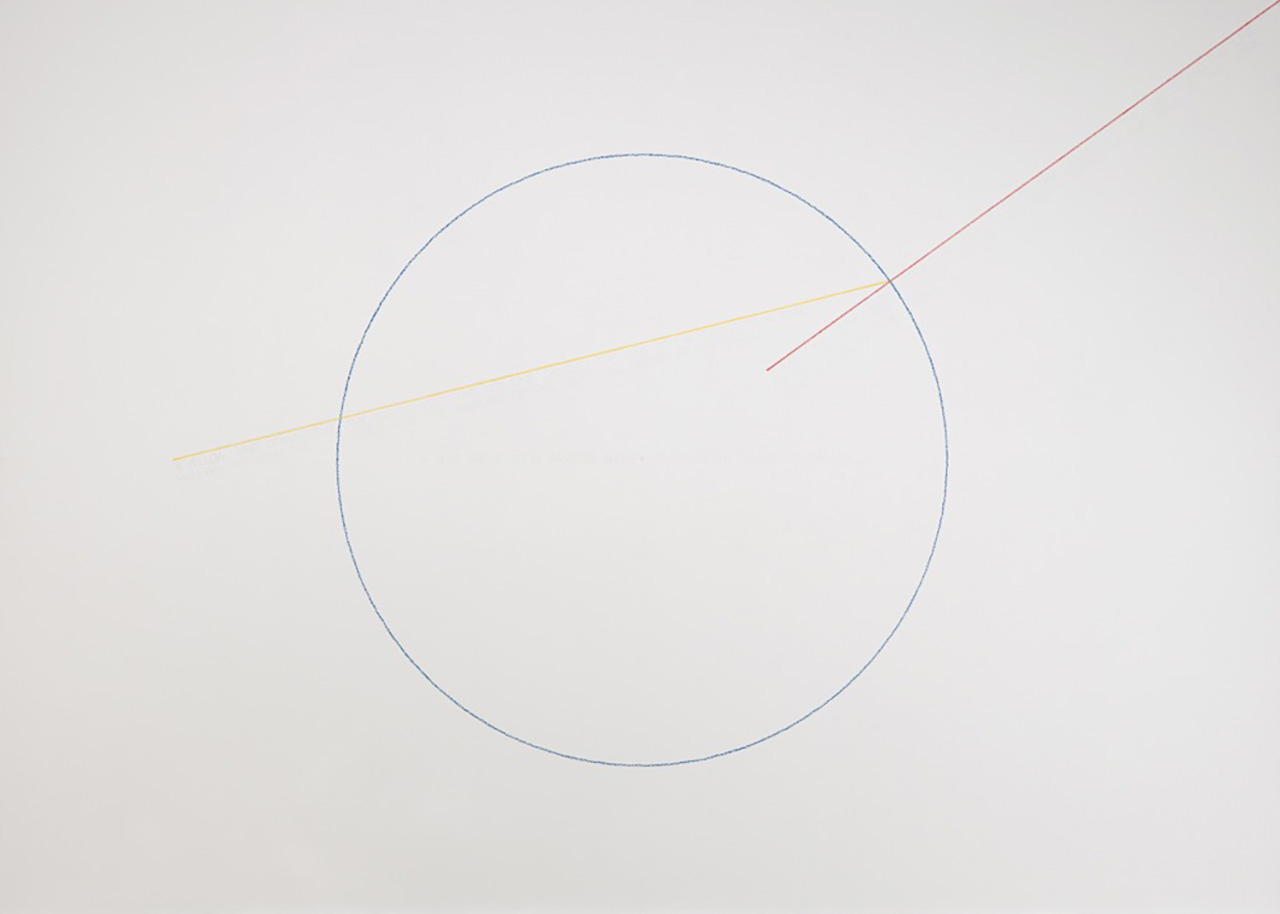

Sol LeWitt: Open Structure

2026.02.16

Artisan

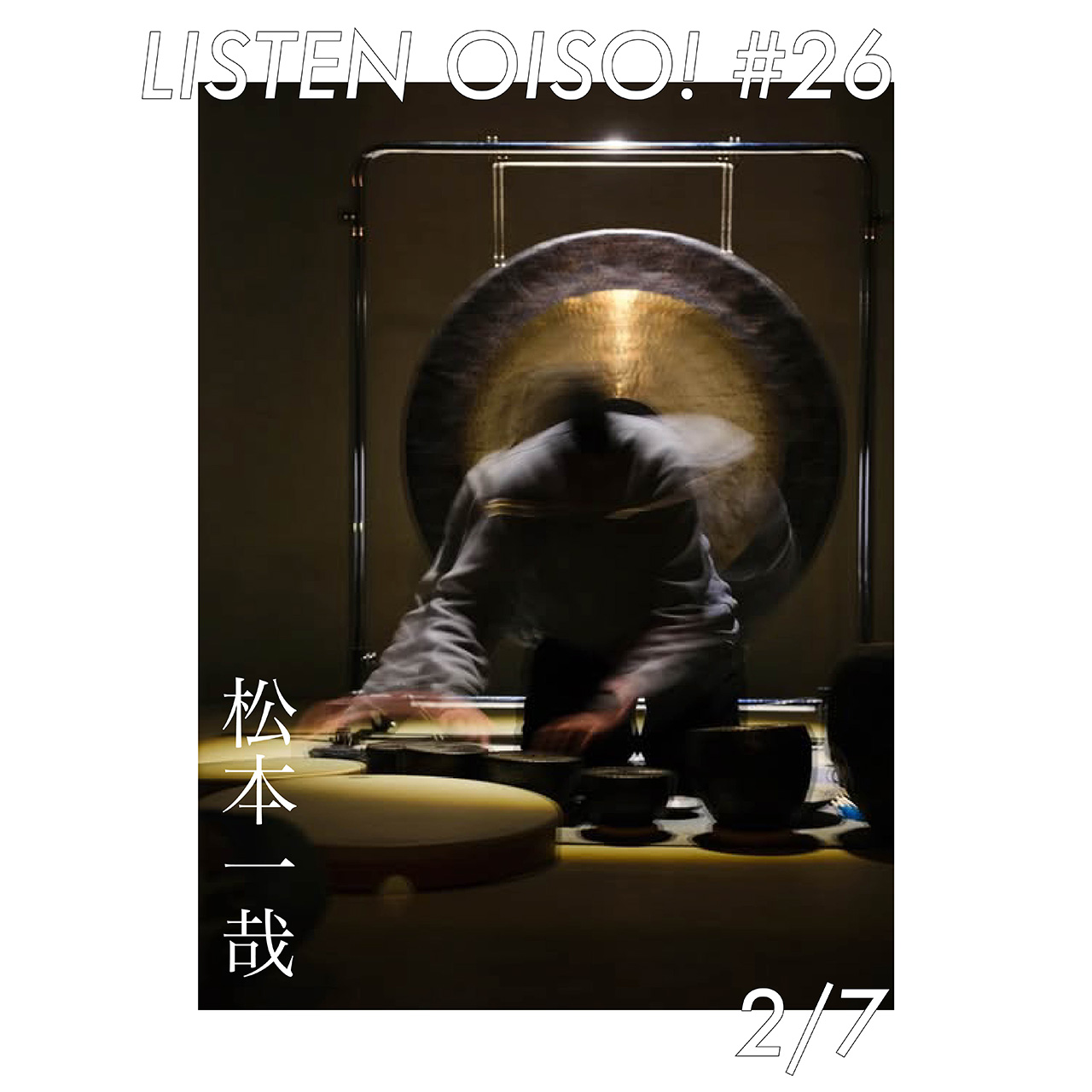

LISTEN OISO! #26

Daysuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsuda, and Kazuya Matsumoto

2026.01.26

Artisan

Lingering Memory / Michiko Van de Velde

2025.11.12

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025