Artisan

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photo: Keisuke Fukamizu

2022.07.19

A small, sturdy frame and tanned skin. Faded work clothes and muddy boots. Although Sadao Yasumoro exudes the aura of strength of those who have spent many years working with their bodies, he is not at all overbearing. In fact, I might even call his affable expression adorable, to the point where I couldn’t help but smile when we met, though this might be a disrespectful way of talking about a master of gardening, universally known by those aspiring to the craft. But the witty jokes flew from his mouth so fast I instantly forgot my concern, entering a state of pure enjoyment. He has the kindness of a natural host.

Yasumoro turns eighty-one(at the time of the interview) this year, and in a career spanning more than fifty years he has designed such highly regarded gardens as those at the Myoteiin temple built by Ieshige, the ninth Tokugawa shogun; Yushima Tenmangu shrine; Hakone Suishoen resort; Le Parc Hotel (France); Lotte Hotel (Korea); and the residences of Soichiro Honda and Ryuzaburo Shikiba. He not only directs the overall composition but takes part in the physical work of gardening as well. Said to be the last craftsman to carry on the many skills and techniques that go into a Japanese garden, Yasumoro’s creations are classically elegant yet interwoven with scenes from the pastoral fields and woods of the Japanese countryside.

“I like the simple earthen walls you see in mountain villages,” he says. “I could have spent my life as a farmer.” These attitudes have won him the admiration and respect of many fellow gardeners. He continues to visit worksites, talking with the younger gardeners on his staff and taking part in their work. I visited him at one such site. During pauses in his work, he shared his thoughts and feelings about gardens, eyes glittering like those of a young boy.

I was born in 1939 into a farming family in Tokyo’s Machida district, the fourth of six siblings. Because there were many children and we were poor, I often missed school to help around the house. I enrolled in Tokyo Metropolitan Engei High School, which has an agricultural focus, but because I couldn’t afford the monthly tuition, one of my teachers suggested I get a parttime job. “How about doing some painting and field work for Teizo Niwa, the scholar of landscape gardening?” he asked. Professor Niwa was a leading authority on Japanese gardens who established the categories we know so well today, such as karesansui (rock gardens), kaiyushiki-teien (stroll gardens), and rojiniwa (tea gardens). On top of being a scholar, he was the type of person who wasn’t satisfied unless he did something himself. For instance, he would measure the difference in temperature between the concrete inside and outside of a lawn, and he planted over a thousand species in his home garden to study. At the time, he was a professor at the University of Tokyo, so all his assistants other than me were students from his university. He was always getting mad at me for being so dull-witted. Once he asked me to run and get a hand scythe so he could trim the grass in the upper fields, but when I rushed it over to him, he said, “Why didn’t you bring the whetstone, too? When you use a scythe, you always need a whetstone!” I’m sure that if I’d brought the whetstone, he would have asked me why I hadn’t brought a bucket of water, too. But every time he scolded me, his wife would tell me things would be okay.

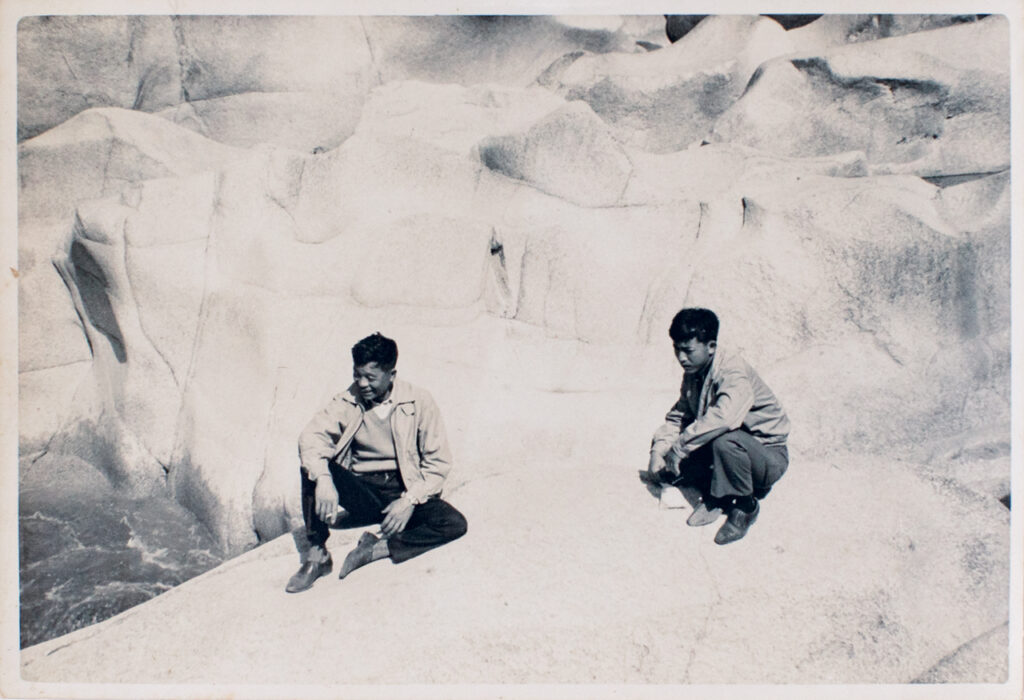

In any case, I learned many things about Japanese gardens by working for Professor Niwa. He told me, “Don’t take the easy path. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Act like you’re at the racetrack, but spend that money on developing yourself.” I took him so seriously that I left on a journey across Japan with no destination. I wanted to meet anonymous master craftsmen in outlying areas. From Aomori in the north to Kyushu in the south, I traveled intermittently from the time I was around twenty-five into my thirties. I was such an inveterate wanderer, I didn’t even stop when I got married and had a child.

It wasn’t unusual for me to get tired or hungry while walking and lay down by the side of the road. Once, on my way somewhere, I stopped at the Tsuki No Katsura garden in the city of Hofu, Yamaguchi Prefecture. The owner of the garden, Setsuro Katsura, dumped a bucket of water on me. After that, he told me to take off all my clothes. I must have been really filthy. He brought me fresh clothes and fed me, and I ended up staying there for about a week. After that he gave me some money to get home, but instead of going home, I headed for Kyushu! Point is, Tsuki No Katsura was a wonderful garden. It was designed in the Edo era, and the balance of rocks, the use of borrowed scenery, and structures were all outstanding.

I saw many fine gardens on my travels, but what I will never forget are the scenes of the countryside—the terraced fields and magaki (walls of coarsely woven bamboo or brushwood) and other landscapes that arose from the necessities of daily life. I think the beauty of that scenery informed my later work.

I started my own business when I was around thirty five. Some friends and I formed a study group and met up regularly. It wasn’t just gardeners—there was a plasterer and a carpenter too. We studied everything from the history of gardens to the practical skills. I learned a lot in that group. That’s how I know about tiles and plastering and buildings, not just plants and rocks. That sort of all-around ability is essential to gardening.

I also often went off to mountains and rivers to look at rocks. After all, you can’t pile rocks in a garden if you don’t know how nature piles them. Even the smallest rock has a center of gravity and a line of flow. You can’t produce something authentic simply by copying the appearance.

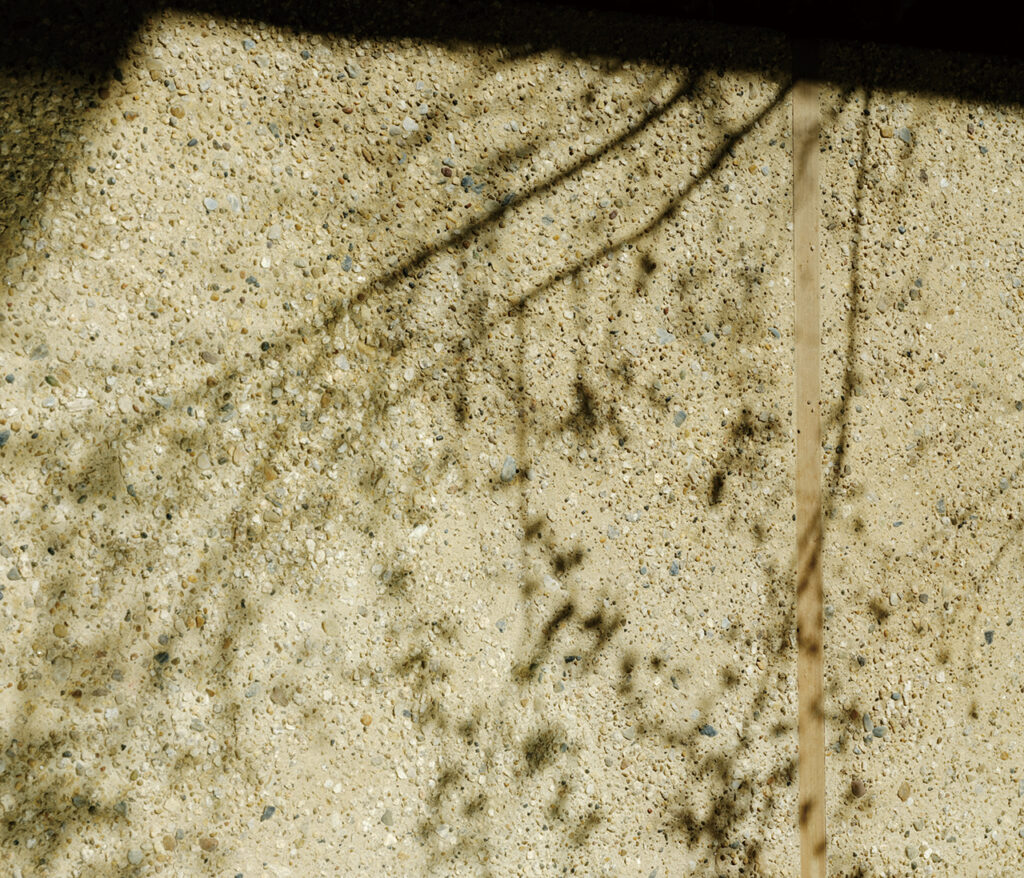

When it comes to earth walls, I like the ones that look like they were built by a farmer. It’s best not to overdo things in a garden. You should use materials that look as if they were laying around the site. So rather than milled wood, I’ll go out to the forest and collect fallen trees. Chestnut logs, things like that. I use an adze to cut six or eight faces on them. I don’t like readymade products. They suit the human body poorly. But I’m a bit of an eccentric!

Even after I started my own company, I continued learning from many people. Antonin Raymond, an apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright’s who came to Japan when Wright was designing the Imperial Hotel, used to dote on me. I visited his office in Kasumicho all the time. He’d say, “Let’s try it your way,” and let me design fences and things. He came by the worksite with his wife Noémi and praised me wildly. He used to make the oddest requests, like “If you sterilize the soil, make sure not to kill the ants,” or “Throw some water on that concrete so it looks wet.” He was a very interesting man.

I’ve also received many commissions from architects like Kiyonori Kikutake, Togo Murano, and Bunzo Yamaguchi. In other fields, I’ve been fortunate to get to know ikebana artist Sofu Teshigahara (founder of the Sogetsu-ryu school of flower arranging), the psychiatrist Ryuzaburo Shikiba, who supported the work of artist Kiyoshi Yamashita, Soichiro Honda (founder of Honda Motor Co., Ltd.) and many others. All of these people were full of wonderful ideas and thoughts, constantly surprising me during our conversations. Of course, they scolded me quite a bit, too.

In the past, many of my clients were knowledgeable about tea ceremony or ikebana or other aspects of Japanese culture. The projects they commissioned were serious and their standards were high, so I had to study hard to avoid coming off as oblivious. These days not many people have the perspective necessary to really see a garden. Lots of people only know about the stock gardens that are made by construction companies, but as far as I’m concerned, their designs are too rigid. Everything’s been decided down to the last detail. They’re either all design or all practicality.

In old Japanese houses and structures, every space had a meaning. For example, in this garden there are some stalks of bamboo lying on the ground to represent the Buddhist concept of kekkai, or boundary. You must not cross a kekkai, although you easily could if you had the mind to. It’s a kind of custom telling us, “Everything past this line is sacred.” Another example is the rojiniwa outside a teahouse, which serves as a device for distancing visitors from ordinary life and worldly concerns before they join a tea ceremony. Rojiniwa have something called a chiriana, which literally means “dust hole.” It’s where you empty out the dust that’s accumulated in your heart—a place to leave behind hateful or regretful thoughts toward other people so you can drink tea in a tranquil state of mind. Gardens and houses had spiritual elements like that in the past. They taught people how to live.

Gardens have what’s called jiwari, which is a system for dividing space. The area from the entrance to the gate is called the montei (gate garden), and beyond that is the shutei (main garden). Further on you have the uraniwa (back garden) or chatei (tea garden). At temples, you’ll find a path of beautiful, smoothly quarried stone leading from the gate to the main temple building. Since people of all ages and circumstances walk down this path, it’s designed so that no one will stumble. If you put down steppingstones in a place like that, people in a hurry would fall flat on their behinds! But as you move toward the back of the precincts, you will find steppingstones as well as nobedan (a path made from stones set right up against each other). To compare it to Japanese calligraphy, the montei has the effect of kaisho (regular script), after which you gradually transition to gyosho (semi-cursive) and finally sosho (cursive). These days, that sort of consideration and spirituality has been forgotten, or preserved in form only.

The photographer Taikichi Irie, who took many pictures of old temples and statues of the Buddha, has pointed out that the Buddha is usually bent forward slightly. Similarly, we tilt rocks forward slightly when setting them in gardens. Contemporary scholars and landscape designers who don’t know about that will say “the rocks are nodding off” and wake them all up. But somehow when the stones are pointing straight up, they look like they’re putting on airs.

Because gardens have souls, the feelings you have when you go there are very important. You need a certain receptivity or playfulness. I listen to the client’s requests, then create the garden as if I were painting a picture on a blank canvas without so much as a preliminary sketch. I don’t draw up quotes or blueprints.

In the course of visiting the site many times, my ideas change over and over. Folks say I make “moving blueprints.” To state the obvious, nature changes moment by moment, so the garden is not complete when the last stone is set. The garden is alive and continues to grow.I watch gardens changing day by bay, so I tend to think decades into the future—should I lay this at a slant? Maybe I should try setting it like this, so it looks about ready to fall? I’m still learning every single day. Recently, in a project for a shop, I got permission to make a large araidashi floor (a type of floor for semi-exterior spaces in which pebbles and gravel are mixed into the mortar before it’s laid down, after which some of the cement is washed away, leaving the stones exposed). It brought back a childhood memory of playing in the dirt with my mother’s precious powdered food coloring, which she used for coloring mochi. So I mixed up some colors that I found calming and had the plasterer use them in the mortar. The look of the floor divided into sections by the joints reminded me a bit of a Mondrian composition. I’d like to try it again with different materials, because some of the unfinished stages were quite interesting.

It goes to show that if you don’t stay involved in the work, you won’t come up with new ideas. I say go ahead and try out any idea you come up with. It’s important to value your own feelings and aesthetic sense. I tell my apprentices, “Don’t think of what you’re doing as helping out with Yasumoro’s work. Think of it as your own work.” As Fujio Akatsuka wrote in one of his mangas, “This will do!”(Reprinted from Subsequeznce vol. 3)

Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

Sol LeWitt: Open Structure

2026.02.16

Artisan

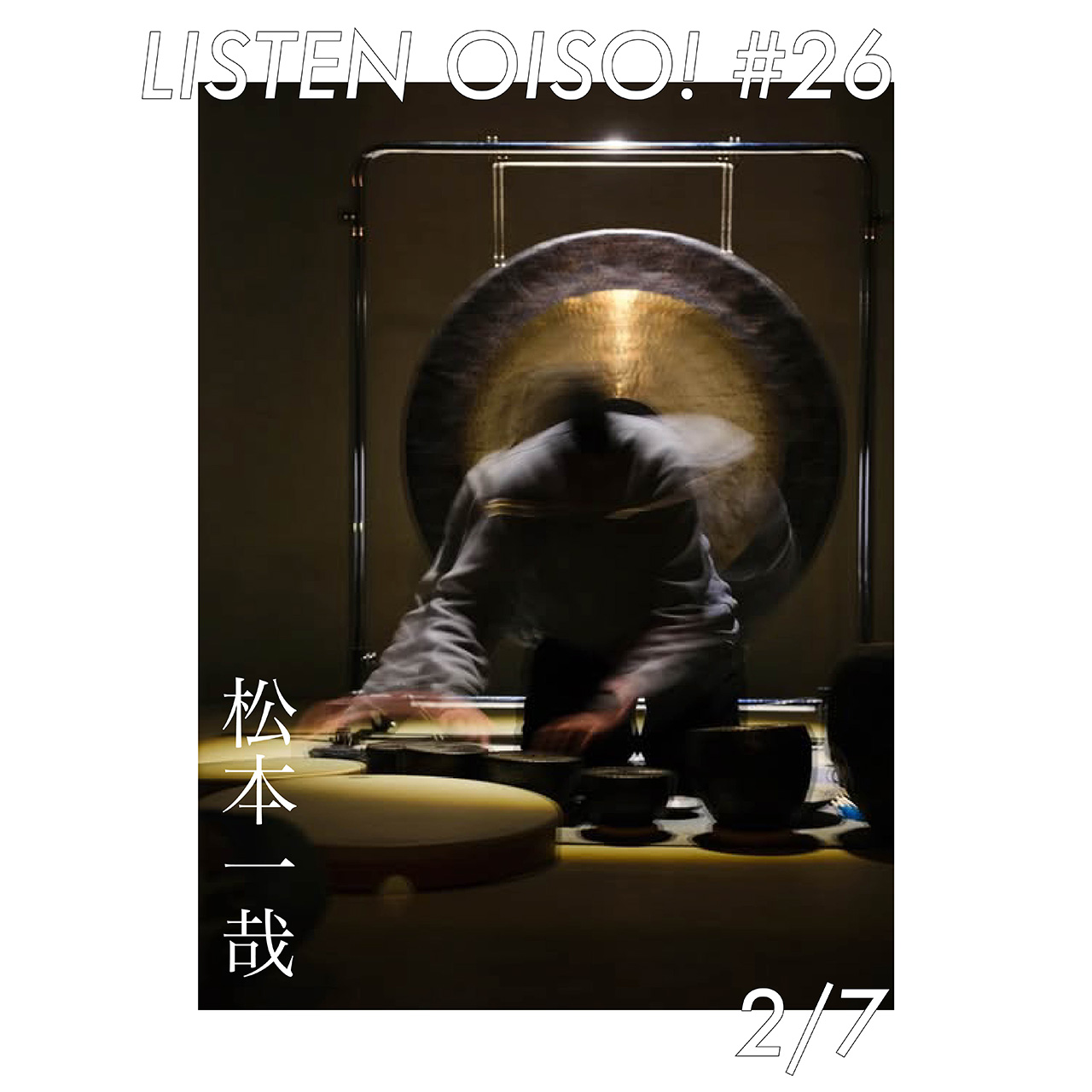

LISTEN OISO! #26

Daysuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsuda, and Kazuya Matsumoto

2026.01.26

Artisan

Lingering Memory / Michiko Van de Velde

2025.11.12

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025