Artisan

The Legacy of Potter Warren MacKenzie

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photo: Keisuke Fukamizu

2023.04.04

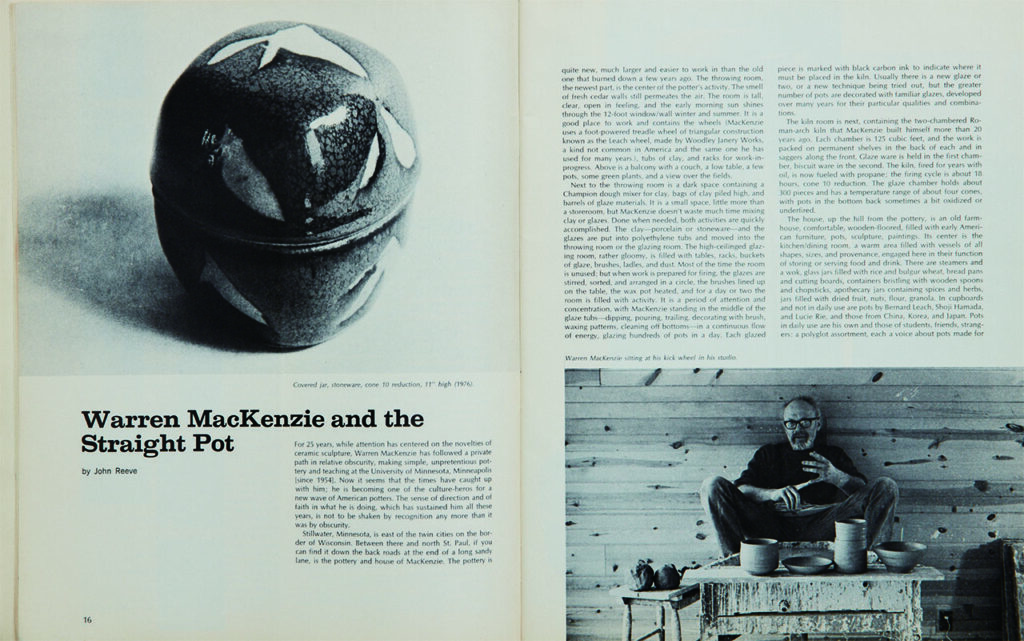

Making functional pots for everyday use – this was the mission of American potter Warren MacKenzie, who for over 65 years created “pottery for the people” in his studio in the countryside of Minnesota, in the Midwestern United States. Influenced both by his early apprenticeship with British potter Bernard Leach and by the Japanese Mingei folk art movement, he was also an educator who built a community of Minnesota potters and communicated the spiritual culture of the region over the years. In search of MacKenzie’s legacy, we set out on a journey to his studio.

Late it the evening on New Year’s Day this year, tired of sitting around the house over the holidays, I turned on my laptop and was scrolling aimlessly through social media feeds when a particular article halted my gaze. “World-famous Minnesota potter Warren MacKenzie dies at 94,” read the headline from MacKenzie’s local daily. According to the article, he had died peacefully on the morning of New Year’s Eve. I wanted to react solemnly to his quiet passing, which at his age could only be called natural, yet as I burrowed my chilly body under the blankets I couldn’t shake a certain restless agitation. The truth was, I felt a pang of regret that I would never be able to meet MacKenzie in person at his studio, a wish I had long harbored.

As the newspaper article claimed, MacKenzie was indeed a “world-famous potter,” but at least in the Japan of 2019, one can’t exactly call him widely-known. A quarter century earlier in 1994, however, it was Japanese companies that produced an invaluable documentary about the potter at age seventy, and the next year put out the only retrospective published during his life. That short film titled Mingeisota introduced me to MacKenzie’s life and turned me into an admirer (the film is still available for viewing in its entirety online, and I highly recommend it to anyone with an interest). The scenes of the potter at work in his Minnesota studio were fascinating, as were those shot in St Ives, England, where he studied as a young man at the pottery studio of Bernard Leach, but what struck me most was the powerful resonance that MacKenzie felt with Japan’s Mingei movement, to which he had been exposed through the potter Shoji Hamada.

Thanks to his consummate skill, MacKenzie was able to produce large quantities of pots very quickly.He intended for these pots to be used by ordinary people in their everyday lives. Alongside his second wife Nancy, he threw pots on the same type of treadle wheel he had grown accustomed to at Leach Pottery, and once a month fired them in a gas kiln that could hold 600 to 800 items at once. His work had the warmth, simplicity, and ruggedness of handmade crafts, evoking the essence of the Mingei movement. He displayed his finished work in an unstaffed showroom adjacent to the studio and sold pieces through the honor system, which helped keep prices down. In the film, he is shown attaching a sticker to one of his pots marked with the astoundingly low price of six dollars.

In addition to his career as a potter, MacKenzie worked throughout his life as an educator. He taught at the University of Minnesota and held workshops in the United States and abroad. The documentary shows students from a nearby middle school visiting his studio and watching him work. Potters began to gather in Minnesota, drawn by this artistic and educational dynamism, and eventually the state became known as a thriving center of ceramics culture. The film’s title, Mingeisota, is the term used to describe the community of potters that formed around MacKenzie.

News of Warren MacKenzie’s death attuned me once again to his life, and several months later I found myself suddenly wanting to visit Minnesota. Even if I would not be able to meet MacKenzie, I thought that perhaps some trace of him might remain in his beloved Mingeisota. At the end of June, my team and I bought tickets bound for Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport. Through research I had learned that the studio where MacKenzie worked for so long was still in operation, and managed to get in touch with the potter Olivia Jenson who had taken things over. Olivia, who is just 22 years old, replied to my email with a warm invitation to visit.

“10,000 Lakes”- as its license plate so proudly announces, Minnesota abounds in forests and freshwater. Located just south of Canada in the American Midwest, the state can experience temperatures as low as minus 20 degrees Celsius in the depths of winter. Perhaps this familiar climate accounts for the

large number of Europeans hailing from Scandinavia who settled here.

Even today about a third of Minnesota residents have a Northern European background.I left the metropolis of Minneapolis and headed east about thirty minutes, watching beautiful conifer forests pass by outside the window. In the woods beyond the town of Stillwater, I spotted a small building with walls made of old corrugated metal and a brick chimney poking from the roof. This was MacKenzie’s studio.

Olivia responded to my knock on the door dressed in an apron and greeted me enthusiastically.

“Hi! Welcome!”

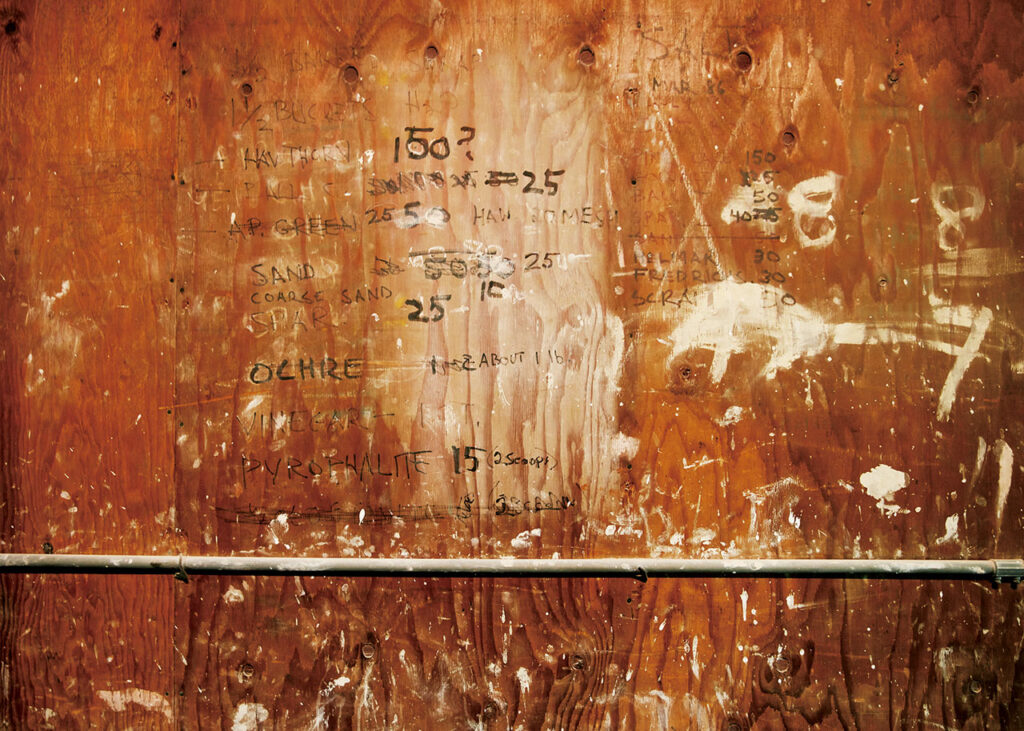

The inside of the studio looked like it hadn’t changed a bit in the 25 years since Mingeisota was filmed there. “Warren was still making pots here two-and-a-half months before he died,” Olivia told me. The wellused potter’s wheel, the pug mill, the cardboard box of clay labelled “MacKenzie Special,” the spatulas and files and other tools, the large gas kiln, the glaze recipes written directly onto the wall, the faded posters of exhibits by the potters Lucie Rie and Shoji Hamada…all of it emanated powerful traces of the recently-departed potter. “I’ve left things just as Warren had them at the end of his life,” Olivia said. When I glanced at the unfired pots lined up in the staging area, I felt as if MacKenzie had been working there just before I arrived.

Born in 1924 in Kansas City, Missouri, Warren MacKenzie read A Potter’s Book by Bernard Leach as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was awakened to the appeal of making functional pots for everyday use. After graduation, he and his first wife Alix (Alixandra Kolesky MacKenzie), a university classmate, took teaching positions at Saint Paul Gallery and School of Art and relocated to the area. However, realizing that they did not yet have the skills to teach pottery, they traveled to St Ives, England and asked Leach to take them both on as apprentices. At first Leach turned them down for lack of skill. Persistent, they visited his studio frequently for two weeks, during which time they formed something of a connection. A year after they returned home to Minnesota, Leach at last granted them permission to study with him. The two spent the next two-and-a-half years living and working in Leach’s home. Warren was 28, Alix was 26, and Leach was 63.

Working alongside Leach, MacKenzie gained the skills to throw fifty pots a day and discussed many aspects of the craft with the older potter (he later recalled that they engaged in heated debates at times). He also became familiar with Leach’s large collection of ceramics and was strongly drawn to the work of his close friend Hamada, with whom the master had founded Leach Pottery, his studio. MacKenzie was powerfully influenced by the Mingei philosophy of making pottery for common people and seeking beauty in utilitarian objects born of the local environment, which both senior potters shared. He later said that even more than his work at Leach Pottery, where skill and meticulous planning were used to produce precise forms, it was Hamada’s pottery, particularly its pursuit of distinctive expression through improvisational dialogue with clay and glazes, which taught him the most.

After completing their apprenticeship, Warren and Alix had the opportunity to meet Hamada in person at the International Conference of Craftsmen in Pottery & Textiles in Devon, England. In 1952, after returning home, they invited Hamada and Soetsu Yanagi to Minnesota during their tour of America and organized Hamada’s first major U.S. exhibition at the Saint Paul Gallery. Their relationship with Hamada continued to develop, and in 1974 Warren visited Hamada in Mashiko, Japan.

In 1953, Warren and Alix found themselves a barn on an old farm outside Stillwater and set up their own studio there. At the time very few other potters lived in the area. Warren taught at the University of Minnesota and started throwing pots. Alix mainly handled decorative elements, adding beautiful designs to Warren’s work. They spent their days caring for their two children and making pottery together. However, in 1962, Alix died suddenly of cancer. In the midst of those dark days, another painful incident befell Warren when the studio burned to the ground in 1968.

The current studio, built after the fire, is already half a century old. In 1984 MacKenzie married his second wife, Nancy, a textile designer (who passed away in 2014). He continued to teach and tirelessly create “pottery for the people” for the remainder of his life.

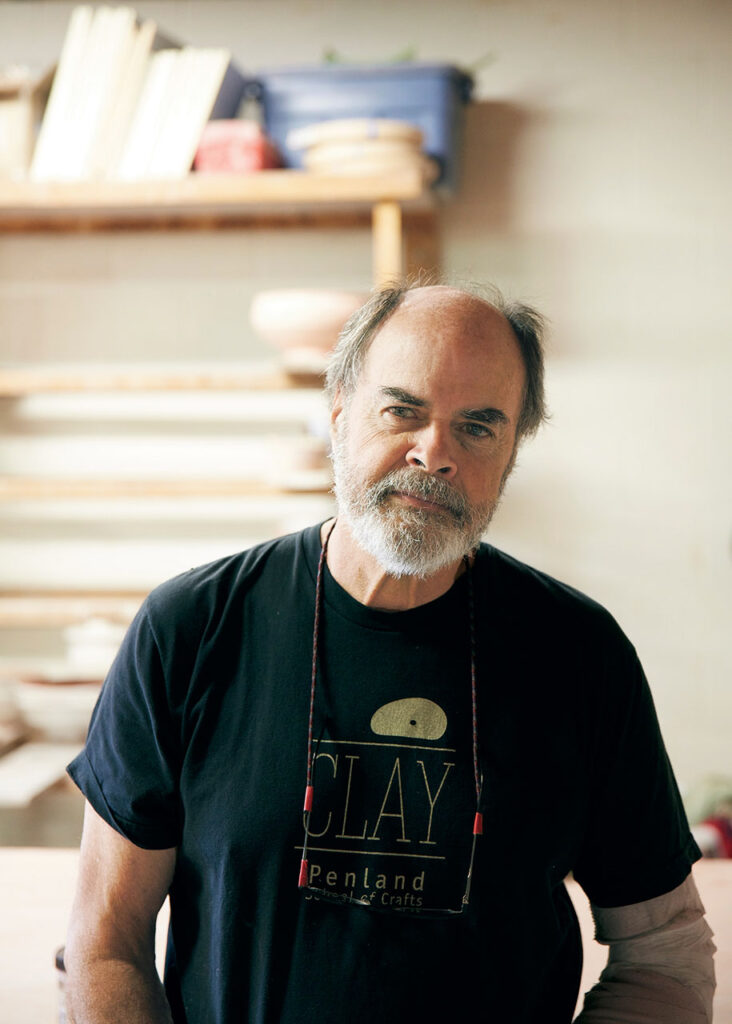

“I was in the pottery program at the University of Minnesota, that Warren started back in the day,” Olivia told me. “But I’m from Stillwater, so I already knew who he was. I’d visited this studio in high school. From then on, Warren was my idol. Two years ago I heard he was looking for a young assistant and he accepted me right away. Warren had an egalitarian nature, so our relationship was very open – more like studio mates than teacher and student. He was a very tolerant and warm person.”

Olivia’s recollections gave me a sense of MacKenzie’s teaching style. Thanks to his longstanding activities, Minnesota today is a thriving pottery region where both children and adults have many opportunities to experience ceramics culture. Raised in that environment, Olivia continues to make pots in Warren’s studio, using the same clay and tools that he used as she throws pots on a traditional wheel. Even the use of carbon ink to identify glazes is a tradition handed down from Leach Pottery, she said.

“Warren taught me about the Mingei view of crafts, and for the first time I realized that those objects were art, too. It was huge for me that I was able to learn about life and nature and hospitality from him,” she said.

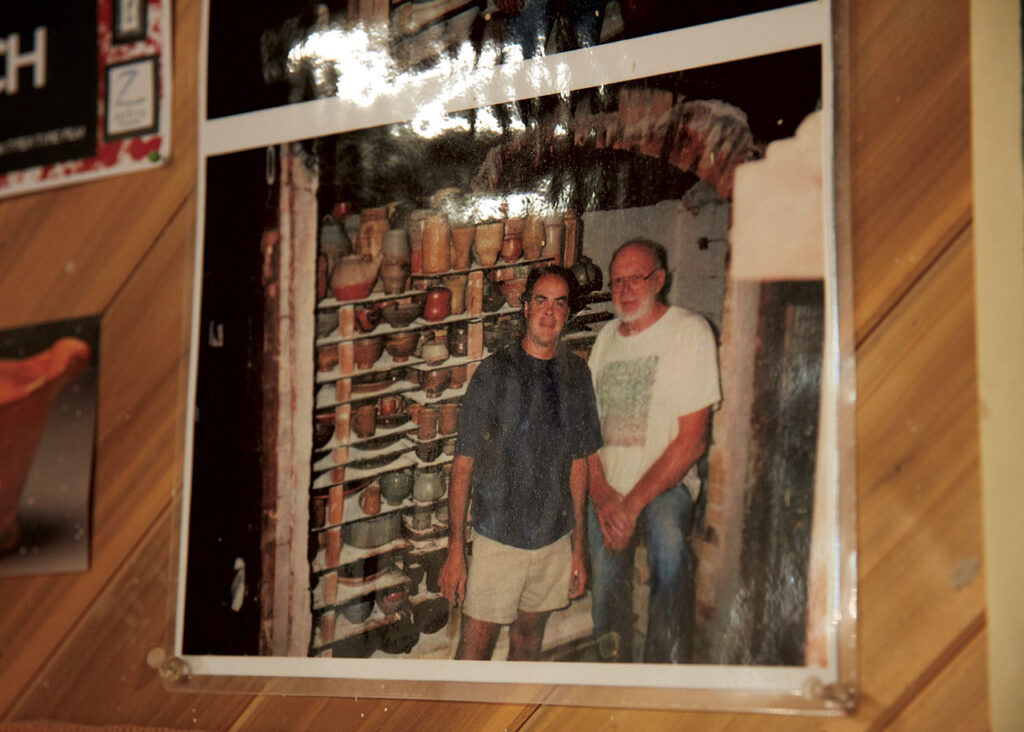

I heard that a friend of MacKenzie’s had a pottery studio in the town of Shafer, an hour north of Stillwater by car, and I decided to drive up to see him. Guillermo Cuellar grew up in Venezuela and met MacKenzie at a workshop there in 1981. He spent the following twenty-some summers working alongside MacKenzie as his assistant. In 2005, Guillermo moved to Minnesota with his wife, and has been making pottery ever since along the upper reaches of the St. Croix River.

Guillermo welcomed me warmly to his home and studio, which is surrounded by a spacious yard. He will turn 68 this year, and struck me as a quiet but dignified man.

“I studied pottery at a university in Iowa,” explained Guillermo, “and I, too, was influenced by Leach’s A Potter’s Book. After graduating, I worked for the World Wildlife Fund in Venezuela for three years, and that work brought me into contact with the wonderful crafts of the indigenous people. Their thatched houses, their baskets, their carved wooden canoes…everything they used in their daily life had such beauty. After that, I made up my mind to be a potter, and that was when I met MacKenzie.”

The living room of Guillermo’s house was filled with Venezuelan folk art, pots by MacKenzie, and many of Guillermo’s own pieces. His large and small plates, teacups, teapots, tiles, and rice bowls radiated a strength and faithfulness to tradition that struck me as falling in the lineage of Leach, Hamada, and MacKenzie.

“I try not to use the word Mingei when I talk about my own work, because Mingei is a Japanese philosophy. But I think that through MacKenzie I inherited the spirit of making utilitarian pots, which has been cultivated over a long history reaching far into the past. I want to be part of that tradition,” Guillermo said.

Just as MacKenzie once did, Guillermo set up a showroom attached to his studio to sell his work. Predictably, the prices are within the range of what ordinary household goods might cost.For someone used to the price tags on “ceramic art,” they are surprisingly low in relation to the quality of work.

During his life, MacKenzie expressed strong resistance to selling his work for more than one would charge for ordinary household items. He hated the fact that his name caused prices to skyrocket, so much so that he eventually stopped signing his work. Even in old age he continued to singlehandedly produce huge quantities of pots, always striving to maintain reasonable prices. For him, I believe, that was an important element of “pottery for the people.”

Today Minnesota is full of ordinary people who use this type of pottery on a daily basis. When Guillermo told me he was planning to hold an open studio in his garden with several local potters the following day, I decided to come back and check it out. Sawhorse tables had been set out among the lush green trees and piled up with all sorts of pots for sale. It was a beautiful day, and neighbors young and old arrived in groups of two and three to pick up and examine the pots, chat for a while, and shop. Several young potters, including Guillermo’s daughter Alana, who had taken up pottery full time two years earlier, were opening the salt-fired kiln that they fired several days before. The instant they opened the door, gasps arose from the gathered spectators. Everyone stared raptly at the contents.

Far from art authorities or celebrities, these artists were ordinary citizens, each enjoying pottery in their own way. As I watched the scene, I thought that perhaps this was what MacKenzie had dreamed of and spent so many decades creating.

Linda Christianson is a potter and friend of Guillermo who also knew MacKenzie for many years. Like MacKenzie, she keeps her studio and residence in the midst of quiet woods near Lindstrom Lake, just northwest of Shafer. “I wasn’t a student of Warren’s – I was adopted into his forum of ideas,” she told me with a grin.

“I met Warren in the fall of 1977, when he invited me to be part of his annual studio sale, which also included weavers and papermakers. At the time I was studying pottery in Canada and had just built a wood-fired kiln. I devoured Soetsu Yanagi’s The Unknown Craftsman. His way of thinking fit me just like we belonged to the same family. I often talked with Warren about pottery at his house.

He was like a missionary for folk crafts. He poured his affection into beautiful handmade things from anywhere in the world. It wasn’t just Japanese Mingei crafts. He was truly a quiet, kind champion.”

A certain beauty inhabits the handmade objects of daily life that have evolved over long spans of time. Warren, I think, was not only influenced by Leach, Hamada, and the Mingei philosophy – he also drew inspiration from a more universal spirit of craftsmanship that has existed since ancient times. Here in Minnesota, his legacy took root in many places over the decades, and found many successors in the younger generations.

“I don’t imitate Japanese pottery,” Warren said in an interview at age 78. “I think my pots are Midwestern pots. I’m most comfortable in the Midwest. I’m not comfortable on the East Coast or the West Coast, and that may be a very narrow view, but it’s the way I am and so I like it here.”(Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 2)

Guillermo Cuellar’s work are available for purchase on our official web store.

Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

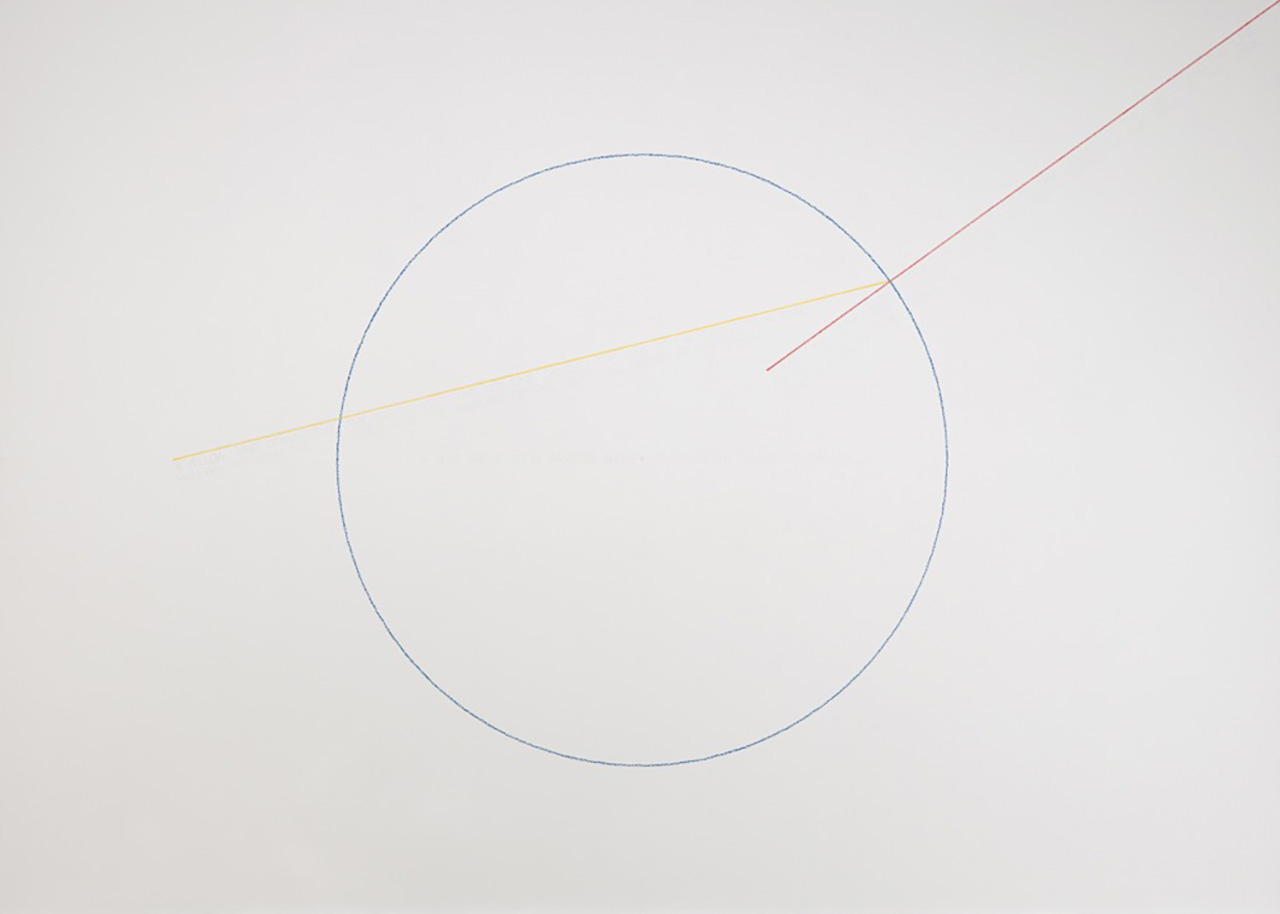

Sol LeWitt: Open Structure

2026.02.16

Artisan

LISTEN OISO! #26

Daysuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsuda, and Kazuya Matsumoto

2026.01.26

Artisan

Lingering Memory / Michiko Van de Velde

2025.11.12

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025