Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

Text: Chisa Sato Photo: Yoichi Nagano

Special Thanks: Shorinzan Darumaji Temple

2023.07.12

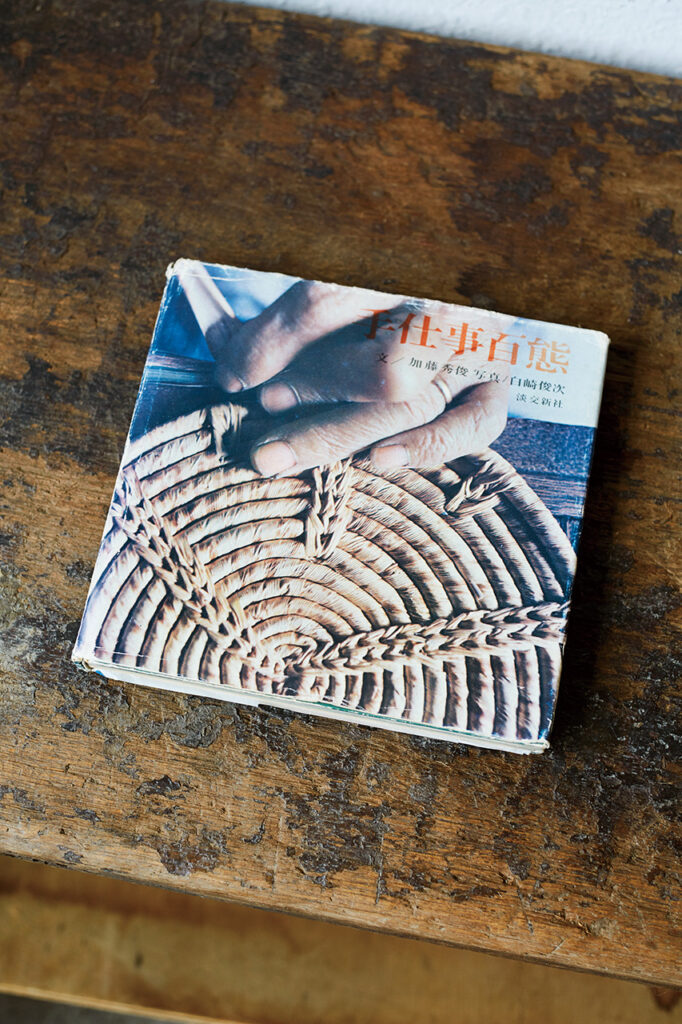

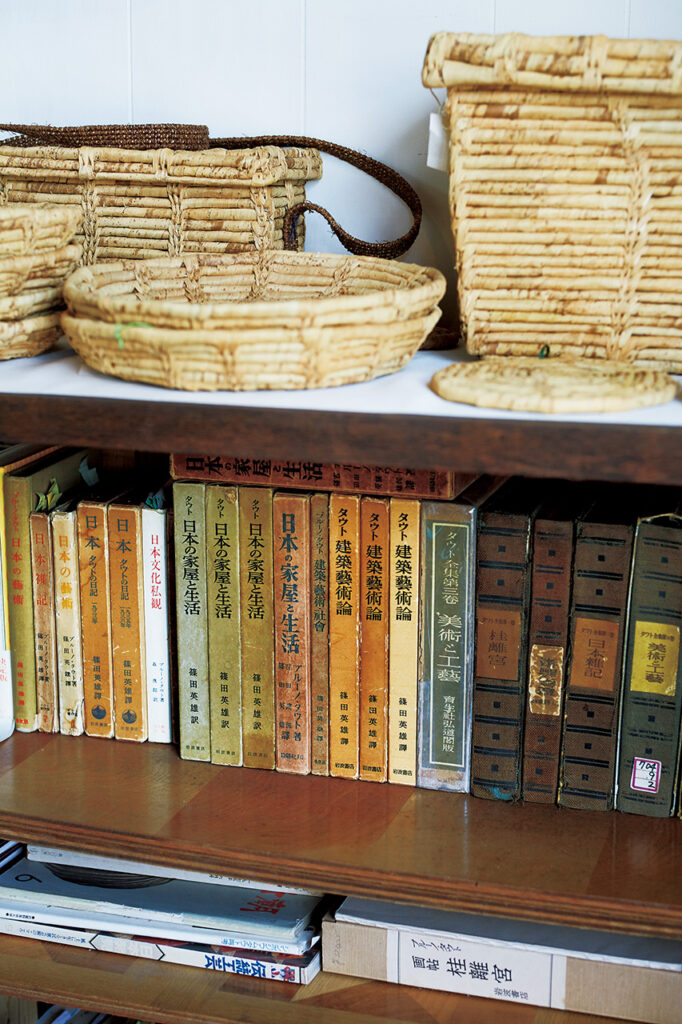

Baskets woven from the papery sheaths that grow around bamboo stalks, simple yet dignified.Adorned with boldly colored geometric patterns and brimming with a curious appeal that evokes the meeting of handmade crafts and modernism, this weaving method was collaboratively developed by the German architect Bruno Taut, who came to Japan in 1933, and the artisans of Takasaki, in Gunma Prefecture. We visited the woman who revived this tradition started by the architect that introduced Japanese aesthetics to the West.

Frank Lloyd Wright and Bruno Taut. Two world-class architects, both unexpectedly thrust into living and working in Japan for several years, influencing the course of modern Japanese architecture in unfathomable ways. Following the Meiji Restoration, a Japanese government desperate to modernize its industries and “catch up” with Western civilization invited a number of architects to work under its employ, including Thomas James Waters, the designer of Ginza’s Bricktown, and Josiah Condor, designer of the Rokumeikan.

This era had ended by the time Wright arrived in Japan in 1913 to discuss plans for the Imperial Hotel, the first of several visits motivated in part by his loss of work back home in the United States due to scandal and tragedy. By the time he left Japan in 1922, Wright had designed numerous buildings and pulled through his long slow period. Meanwhile, the Japanese apprentices involved in these projects went on to leave their mark on the world of Japanese architecture.

Taut, on the other hand, arrived in Japan after a series of coincidences. Born in 1880 in the city of Konigsburg in eastern Prussia, he established an architecture firm in Berlin in 1909 and joined the Deutscher Werkbund, an association which also included Peter Behrens and Walter Gropius. Influenced by England’s Arts and Crafts movement, the group sought to produce architecture and crafts with a level of artistry and quality befitting modern society. The movement can be viewed as a forerunner of industrial design.

Taut was lauded as an avant-garde architect when his Glass Pavilion was displayed at the Cologne Deutscher Werkbund Exhibition in 1914, and received further international acclaim for the 12,000 social housing estates he designed in the outskirts of Berlin, a project that spanned eight years starting in 1924. At the time, Germany was burdened with crushing reparations due to its loss in the First World War, and many laborers lived and worked in

wretched conditions. Taut poured his energy into creating healthy, hygienic homes to improve the lives of these workers.

Energized by the idea of working toward an ideal society, Taut traveled in 1932 to the Soviet Union, where he contributed to urban planning in Moscow among other projects. However, the Nazi party that was rising to power back in Germany deemed these activities a sign of dangerous socialist tendencies. In 1933, Taut learned that the Nazis had issued a warrant for his arrest. He abandoned his flourishing career and post as a university professor to flee abroad with his secretary and romantic partner Erica Wittich. Failing to attain political asylum in the United States, as a last-ditch measure he responded to an invitation from the International Architectural Association of Japan and set out for a country that had interested him for quite some time. He and Erica boarded the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok, crossed the Sea of Japan, and arrived in Tsuruga on May 3rd of that year.

Today, Taut is probably best known in Japan for his role in “discovering” Japanese aesthetics. On visiting the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, he wrote candidly in his diary that it was “so beautiful I wanted to cry,” and in books such as Japan and The Rediscovery of Japanese Beauty, he praises the deep harmony found within the simplicity of traditional Japanese architecture, as seen through the examples of the Katsura Imperial Villa and Ise Grand Shrine. On the other hand, he is harshly critical of Nikko’s highly ornamented Toshogu Shrine, deeming it “kitsch.” By pointing out this lasting opposition in Japanese architecture and indeed Japanese aesthetics as a whole, Taut had a significant impact not only in architectural circles but on the study of Japanese culture more broadly.

The reason that Taut, an architect of international renown, became famous in Japan as an author is the fact that he was not involved in architecture during his time in Japan, with a few exceptions (only two of his designs were ever built). On the eve of the Second World War, when Japan was attempting to strengthen its relationship with the Nazis, Taut, being a political exile, found himself without the kind of architectural commissions he might have hoped for. In that sense, his legacy contrasts with that of Wright and Czech architect Antonin Raymond, Wright’s apprentice, who built many buildings in Japan.

Nevertheless, soon after his arrival, Taut was invited to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry’s Industrial Arts Institute in Sendai, a government agency promoting the modernization and industrialization of Japanese crafts.He took a post there teaching the fundamentals of design theory to students including a young Isamu Kenmochi (later a wellknown interior designer), but lef after just four months, having found little meaning in the work.

With nowhere else to go, he accepted an invitation to the city of Takasaki in Gunma Prefecture from local industrialist Fusaichiro Inoue. After a stint at university, Inoue had spent eight years educating himself in Paris, and upon returning to Japan founded a crafts movement in Takasaki aimed at developing a new, more authentic craftsmanship better suited to everyday life. In addition to running his own studio, he worked as an instructor at the Gunma Prefectural Industrial Technology Research Laboratory, applying his new approach to designing furniture, woodworking, textiles, and other local products. He invited Taut to join him as a fellow instructor. In August 1934, Taut visited Takasaki, and altogether spent two years and three months there – the majority of his stay in Japan, which totaled three years and four months.

Vestiges of Taut’s time living in Takasaki remain. Amidst the bracing air at the top of a steep stone staircase sits Shorinzan Darumaji, a quiet mountain temple. Seishi Hirose, the temple’s current head priest and the grandson of former head priest Daichu Hirose, who looked after Taut during his time in Takasaki, was kind enough to show me Senshintei, the building where Taut and Erica lived.

The wooden building, simple and small but beautiful, peeked out from the cool green leaves of the trees. The two rooms – one six mats, the other a mere four and a half – were meticulously clean and free of clutter. I could sense the care that the Hiroses had taken to preserve the building as it had been in when Taut lived there. During his time in Takasaki, Taut designed 633 craft items, including studies. Somewhat self-derisively, he referred to this period spent writing and designing crafts, unable to practice his primary profession, as “an architect’s vacation,” but he loved the lush nature surrounding his temporary home and the kindness of the villagers and the priest’s family who looked after him. Taut’s diaries from this period include many irritated comments about the difficulty of living in a foreign country, but he also highly praises Senshintei as having “a beauty rare in this world” and writes that “when I return here after traveling, I breathe a sigh of relief.”

“I’ve heard that Taut said the view from here was so beautiful it distracted him, so he used to work with his back to the window,” Hirose told me. “Every day, he ate lunch with my grandfather’s family. Neither household could speak the other’s language, but they seem to have understood one another’s feelings. We have photos that reflect my grandfather’s efforts to welcome Taut and Erica and comfort them when they were far away from home, such as gathering the village children to sing and dance for them.”

Every day, the couple went out walking for two hours, observing village life and architecture and getting to know the villagers. People would call out their names in friendly tones -“Taut-san! Erica-san!”- and serve them tea and snacks, or carry fruits and vegetables to Senshintei. When the nearby Usui River flooded in September 1935, Taut worried about the adverse impact on the community and made a monetary donation. Despite barely having enough to get by himself, he must have felt unable to ignore their plight. Unexpectedly compelled to live among the common people of Japan, he found joy in everyday life and strived to understand the essence of the culture through direct observation. The result was a tradition of Takasaki crafts.

From wooden cutlery and lacquerware to small boxes inlaid with eggshells and washi light fixtures, Taut designed a wide range of everyday objects and furniture. “You can fit the whole world into the smallest of objects,” he said, designing through trial and error a series of items that fused local materials and techniques with modernism.

Among the crafts he designed during this time were weavings made from bamboo sheaths. He adapted a German basketweaving technique, but for his material opted for the outer sheaths of bamboo, which local craftspeople used to fashion a Takasaki specialty called “nanbuomote”, the finely-woven soles seen in the high-end zori and setta traditionally worn with kimono. This was not an established craft, but rather a new technique developed collaboratively by Taut and the nanbuhyo artisans. Taut predicted that as Japanese society modernized and everyday dress shifted from kimonos to Western-style clothing, demand for setta would decline, and hoped to provide a living for the thousand or so people employed at the time in making the woven soles. Together, they developed a large number of designs that brought warmth and color to daily life, including serving baskets, bread dishes, baskets for melons, wine, and knitting, and seats for chairs.

By 1936, Taut had been in Takasaki for two years and grown tired of his exile in Japan. At this juncture, a professor at an art academy in Istanbul contacted the architect, and Taut made up his mind to move to Turkey. On October 8th, a large group from the community saw Taut off as he departed from Senshintei. Only two years later, however, Taut fell ill from overwork and tragically passed away. He was fifty-eight years old.

Many of the craftworks that Taut left behind in Takasaki were lost in the ravages of the Second World War. But after the war ended, bamboo-sheath weaving was revived as a means of livelihood for craftsmen returning from the army, in large part thanks to the efforts of architect and craftsman Yoshiyuki Mihara, who had worked as Taut’s assistant during his time in Japan. Although the designs gradually strayed from Taut’s originals, the industry employed as many as 400 craftspeople at its height in the 1950s and early 1960s, and some items were even exported. But as Japan’s rapid economic growth led to the flooding of the market with cheap, mass-produced industrial goods, demand for handmade crafts declined, and soon production of bamboosheath weavings ceased.

I’d heard that there was a woman in central Takasaki who had fallen in love with Taut’s bamboo weavings and started making them again, so I arranged a visit. These days, Yoshie Maejima is Taut’s lone successor, preserving and sharing the designs that he left behind. Her studio occupies a historic townhouse that has been standing over eighty years and once housed workers from a soy sauce brewery. Dressed in a kimono, she sits in front of a table with knees folded and begins to weave with a long, fat needle also used for making tatami. “It’s like I’m seeing with the cells inside my fingertips, more than with my eyes,” she tells me as her hands confidently coil a strip of bamboo sheath around a core. She says she can complete about one serving dish a day. This is work that requires time and patience.

Maejima first encountered bamboo-sheath weaving about thirty years ago. Originally from the city of Maebashi in Gunma Prefecture, she majored in product design at an art school in Tokyo, during which time she met the industrial designer Yoshio Akioka and took part in the Mono Mono design movement, which sought to change “consumers” into “devoted users.” Later, after working at architectural and landscape design firms, she became a freelance designer and environmental researcher.

“I was in my thirties and ‘searching for myself,’ trying to figure out what I wanted to do. At the time, through work for the Center for Ethnological Visual Documentation (run by Tadayoshi Himeda, a student of the folklorist Tsuneichi Miyamoto), I was involved in a study of the folk customs of

villages in Niigata that were scheduled to be flooded by a dam. There I came into contact with an older way of living, where people made the tools they needed with their own hands, and I began to dream of not only designing things but also making objects with my own hands. I was involved at the time in designs for a park, but I had started to question the value of designing a place for children to play from behind a desk. Around that time, I read an article about bamboo-sheath weaving in a magazine on local culture that I’d happened to pick up.”

From designer to craftsperson making everyday objects with her own hands. In the early 1990s, as Japan’s bubble economy neared collapse, how many other people were focusing on handicrafts like these, rooting themselves firmly in the community? Feeling that she had found her calling, Maejima went to meet the author of the article, eager to begin as soon as possible. The author happened to be Yoshiyuki Mihara, the man who revived bamboo-sheath

weaving after the war. Having won the trust of Taut, he was often called his only Japanese apprentice. Mihara entrusted Maejima with reviving the disappealing local craft.

“Mihara was overjoyed and spent the rest of the day telling me stories about when Taut was here,” Maejima said. “He said he wholeheartedly approved and sent me piles of documents. I think I arrived at a moment when he was getting old and wanted to pass on the technique to someone else. By then about twelve years had passed since production was halted, so this was my last chance to receive instruction from the few remaining practitioners.”

Maejima interviewed these weavers about their techniques, collected written materials, and polished her craft independently. She had always been skilled with her hands -describing herself as the kind of child who made beaded curtains by stringing together watermelon seeds- but she did not have any experience in authentic handicrafts. At first, she commuted back and forth to Gunma Prefecture while continuing to work in Tokyo. Later on, she moved her base to Takasaki and taught design at a local high school while continuing to weave; today she is so proficient at her craft that she is certified as a master artisan. “I brought together the things I love in order to reach the place where I am now,” she says with a gentle smile, radiating unshakable conviction.

Maejima uses a variety of bamboo called kashirodake, meaning “white-skinned bamboo.” Pale, strong, and beautiful, it is a rare variety that grows only in the Okuyame region spanning the municipalities of Yame and Ukiha in Fukuoka Prefecture. This same variety was traditionally used in Takasaki to make nanbuomote sandal soles, but due to the recent decline in demand for bamboo, many of the thickets where it is grown had been abandoned and were overgrown. Determined to save the variety, Maejima founded a grassroots movement in Yame called Kaguyahime (after the folktale about a princess discovered in a bamboo stalk), in an effort to restore and preserve the thickets.

“I organize volunteers and travel to Yame twice a year, for the fall thinning and the early summer harvest. Crafts like these cannot survive unless we preserve the earth that nurtures the materials we use. To me, destroying nature is like wounding the internal organs that sustain our lives. Unless those of us aware of this take action, these craft traditions will die out.

Maejima is a flexible woman of action, filled with the strength that comes from working with natural materials and having deep connections to the natural world. She says she became a bamboo-sheath weaver because she “happened to discover it.”

When Taut developed this craft, he was seeking to contribute to society outside the big cities by tying together modernism and local craftsmanship to create beautiful, high-quality objects. I suspect Maejima was able to recognize the forgotten value of his work because of her own background in design. She took in the stories of the people she met and the character of the objects she encountered with integrity, incorporating them all into her own work. This, perhaps, is the essence of carrying on a tradition. If left undone, the craft would disappear. If she did not share the practice, it would be forgotten. She says that she hopes to work with the community so that these weaving techniques can be passed on to the next generation.

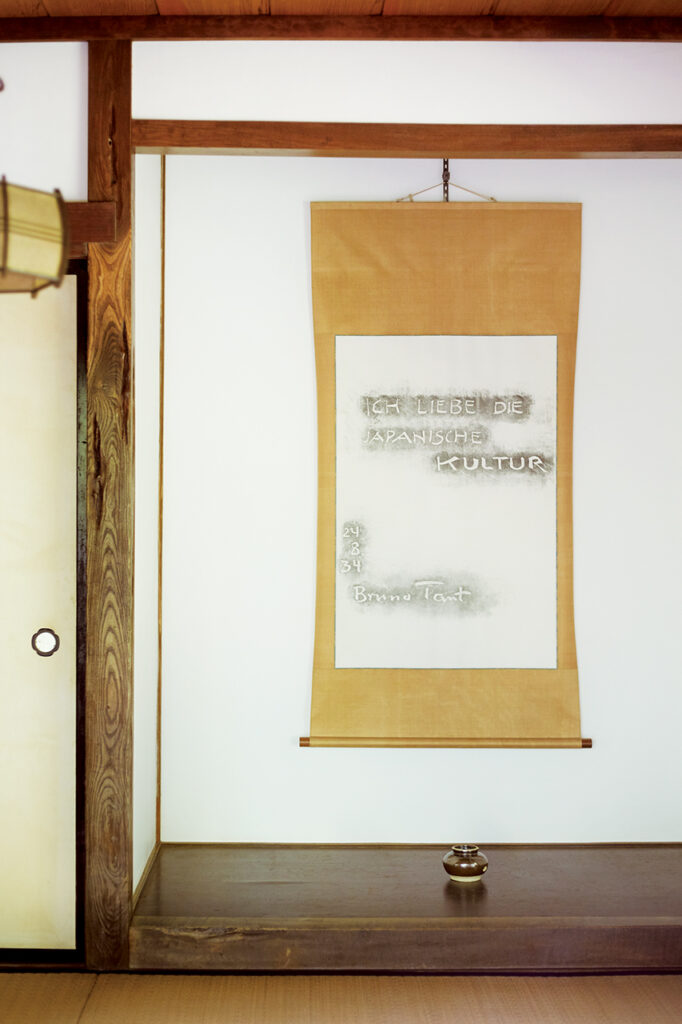

There is a monument at Shorinzan Darumaji Temple engraved with Taut’s words: “ICH LIEBE DIE JAPANISCHE KULTUR (I Love Japanese Culture).” The year after he died in Istanbul, Erica obeyed his wishes and returned to Japan to deliver his death mask to Shorinzan. Forced out of his native land, he had found peace and comfort here, in the natural landscape of Takasaki. Today, that landscape remains intact along with the craft he left behind, carried on in a small way by the community.(Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 3)

Baskets woven from the papery sheaths are available for purchase on our official web store.

Artisan

TAXI DRIVER

2026.02.20

Artisan

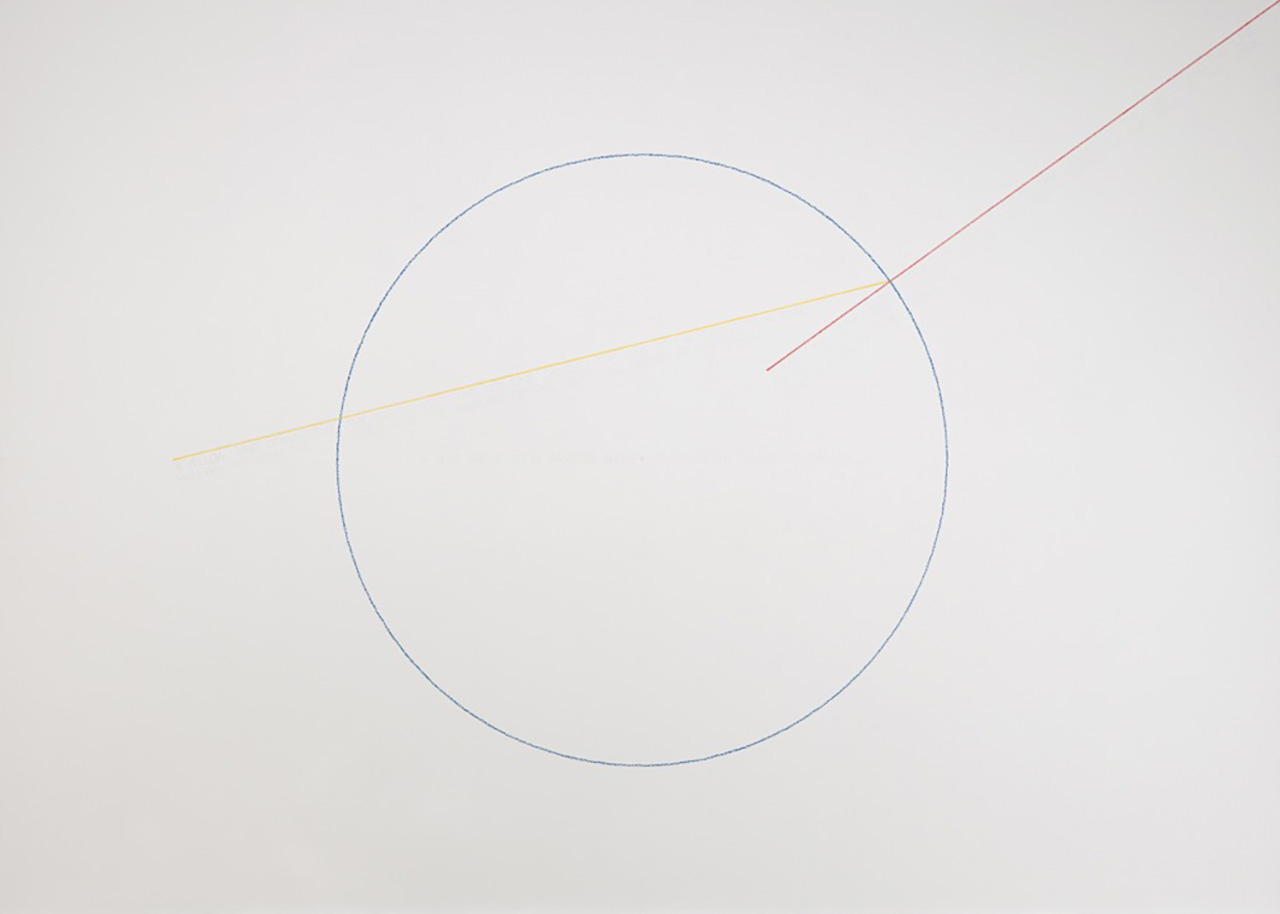

Sol LeWitt: Open Structure

2026.02.16

Artisan

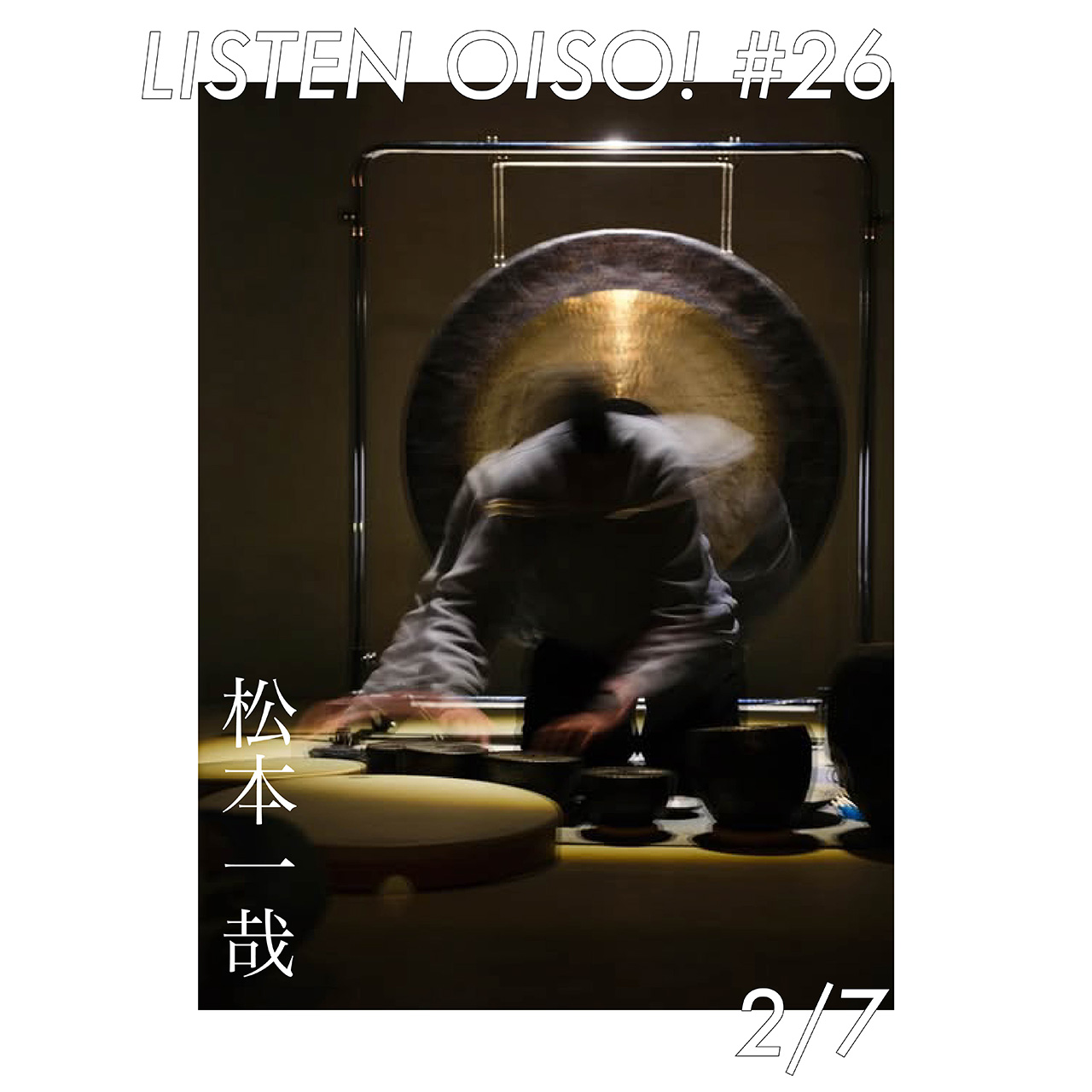

LISTEN OISO! #26

Daysuke Takaoka, Takashi Tsuda, and Kazuya Matsumoto

2026.01.26

Artisan

Lingering Memory / Michiko Van de Velde

2025.11.12

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025