Belongings

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photos: Keisuke Fukamizu

2022.10.12

Situated in one room of a building in Jiyugaoka, Tokyo, the privately operated Iwatate Folk Textile Museum (a general incorporated foundation since 2014) seeks to collect and present dyed and woven goods from all over the world. The collection of museum founder Hiroko Iwatate, gathered over half a century, continues to excite and inspire a great many fashion designers and people working in the arts. Over the years, what has Iwatate been looking for, or hoping to express? We asked for her to share her limitless thoughts on the subject.

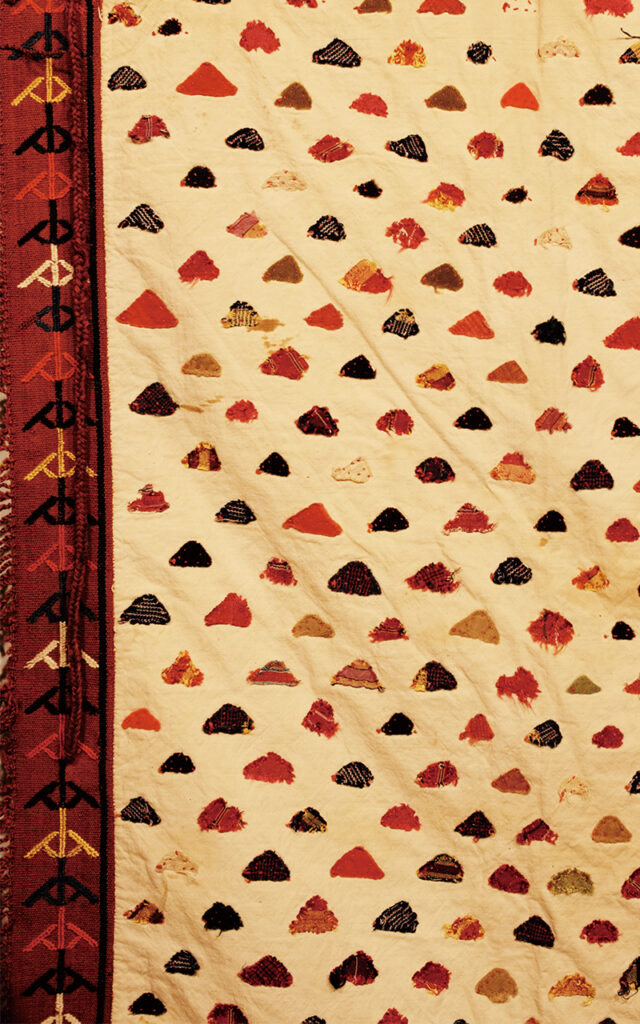

It may be a bit too small to be called a “museum,” but it’s not very often one can see a collection of this volume and quality exhibited in one place. On the contrary, it’s likely that even the best museums in the world would be hard-pressed to match the amount of time and focused dedication that was spent building this collection. Located in a small building a few minutes on foot from Tokyo’s Jiyugaoka Station, the Iwatate Folk Textile Museum houses approximately 7,500 textiles collected from all around Asia over the span of fifty years by its director Hiroko Iwatate.

The collection, which is presented in themed exhibitions that change three times a year, features pieces that were produced before the industrialization of textile production (i.e. up until the mid-twentieth century), with a fair number of items over 100 years old. The majority of the textiles were sourced in their native countries by Hiroko herself.

Hiroko Iwatate was born in Tokyo in 1930 and studied dyeing at Joshibi University of Art and Design, under the tutelage of textile-dyeing artisans Yoshitaka Yanagi and Samiro Yunoki. “At that time, the era of handmade goods was already over. There wasn’t any work when I graduated university, and I really had no idea what I was going to do. That was around the time that I became enamored with Andean textiles from the Inca empire, and in 1965 I spent two months traveling around New York, Peru, Mexico, and Guatemala. What I discovered during my travels was an unchanging, universal beauty. I decided that from that point on, the focus of my work would be searching for this beauty everywhere.”

Seeking a fundamental, universal beauty, unaffected by the changing of the times. Hiroko made her first visit to India in 1970, where she encountered textiles used by the local people. “Natural materials were spun by hand, sewn into cloth, and dyed, then made into veils or sarees.

When the cloth started wearing out, usable parts would be torn off and sewn onto another garment for reuse. This sort of traditional handwork could once be found in cultures everywhere, but it was rendered obsolete by the worldwide obsession with increasing profits and efficiency. That being said, when I began visiting India and the Middle East in the 1970s I could still find items like this at bazaars, and was able to meet people dedicated to reviving handicrafts and vegetable dyeing.”

Although Hiroko is a fervent collector of textiles and is fascinated by the traditional handiwork that is slowly disappearing through continued industrialization, she cautions that her attraction to these crafts cannot be summarized by simple statements like “The older the better” or “The more advanced the better.”

“These designs are not merely conceptual, but come from a place of real meaning. I feel that these kinds of things will not grow old…that there’s a timeless attraction to them. For example, take this decorative camel saddle from Turkmenistan. Women would go around to their neighbors and ask for pieces of fabric from old bridal clothing, then cut them into little triangular shapes and sew them together. Triangles are actually considered a ‘prayer shape’ by these women. I find this absolutely lovely. Don’t you think it’s much more attractive than some stiff, gaudy decoration?”

At a time when information on India and the Middle East was still very limited, Hiroko continued her visits to those far off places, eventually creating a map of textiles. In 1984, she published her fieldwork in a book called Desert Village, Life and Crafts (Youbisha). The year after, she opened a gallery and exhibited the items in her growing collection.

“There’s no point in me being the only one with access to these precious items. Sharing them with the world helps people to hone their senses, and to discover their charms. All kinds of different people come to visit, old and young, men and women, but of course we also see many clothing design students. I remember some exchange students visiting from China, who told me how surprised they were to find garments from Chinese ethnic minority groups in our collection. ‘We had no idea that such amazing things came from our country!’ she said. I’m sure those girls returned home with a newfound appreciation for the beautiful things made in their country.”

This collection features many items of Japanese origin as well; notably traditional noragi and hanten pieces. Fifty years after her first visit to India, Hiroko continues seeking universal beauty and adding items to the collection.

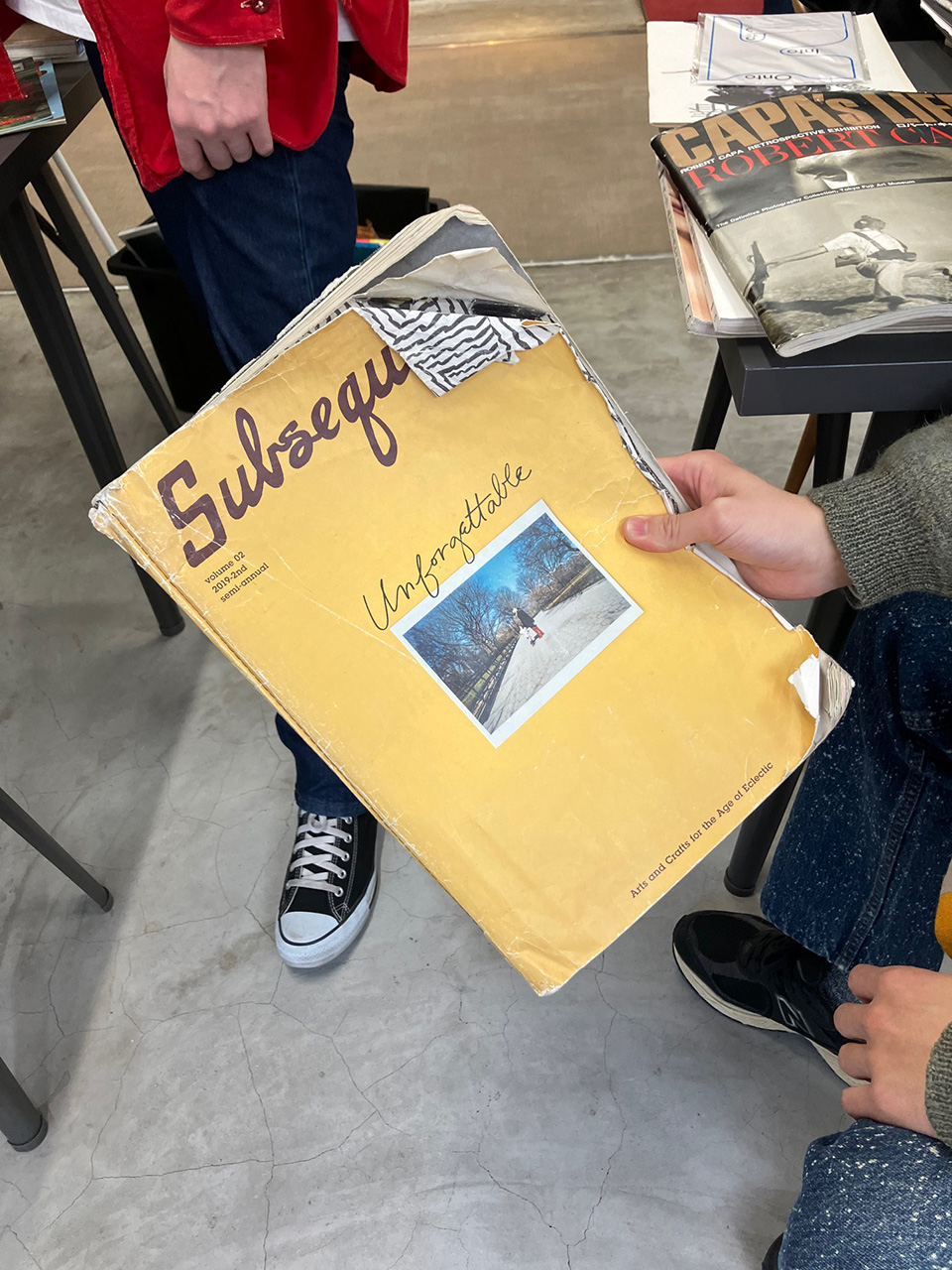

“You can find good materials in any situation. Once you decide that a given generation has nothing to offer, it’s all over. If we can learn to embrace the good around us, the world would be a better place. Even synthetic materials have improved over time. They’re convenient, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with incorporating them into your lifestyle. The important part is to use our ingenuity and continue to create beautiful things. That’s why I’m thrilled to share these charming, antique objects with the world, as modest as the museum may be.” (Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 4)

Some of the textiles owned by the Iwate Fork Textile Museum are available for purchase on our official web store.

Belongings

soma folk

2025.05.26

Belongings

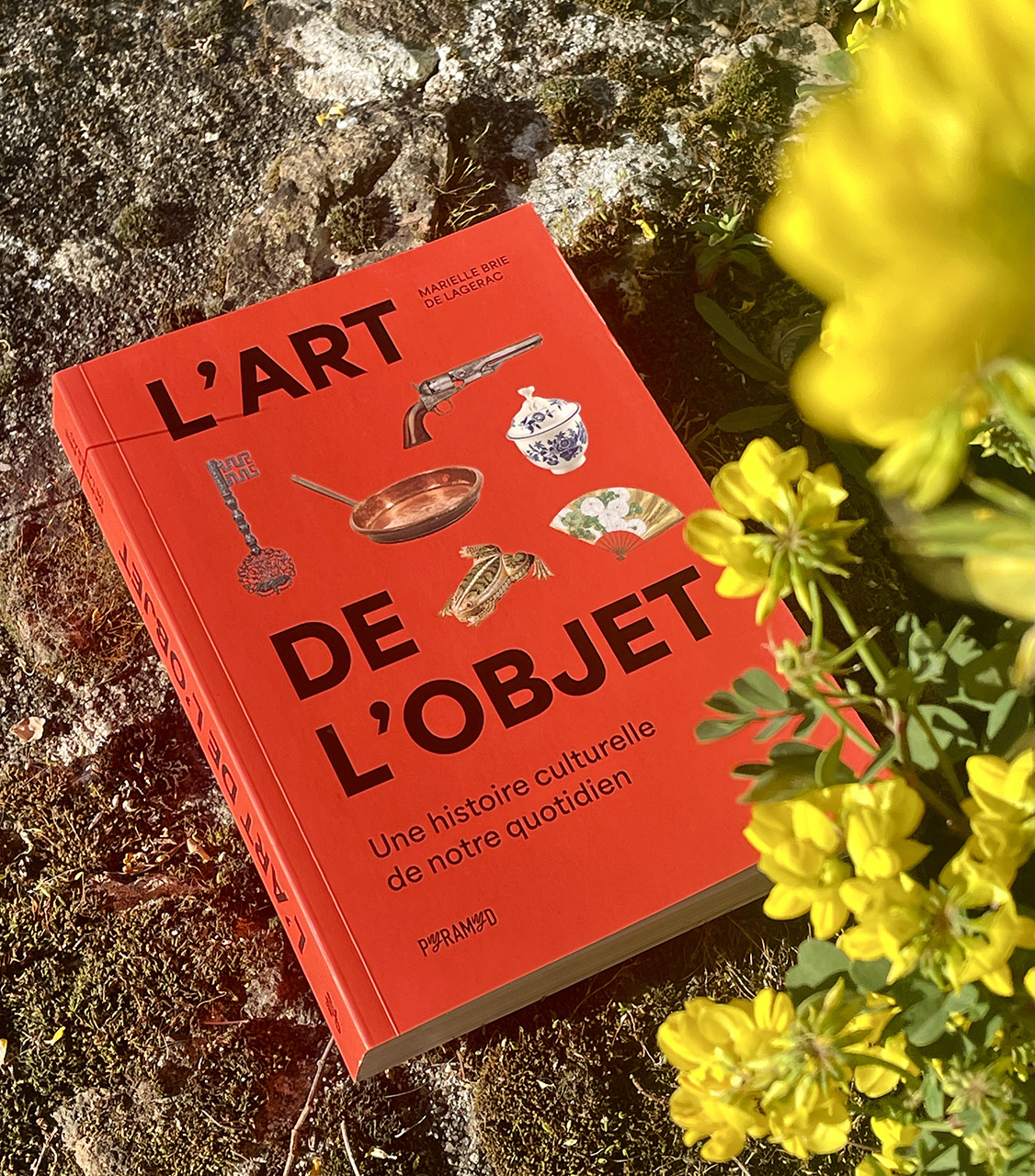

『L’ART DE L’OBJET』

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

2025.04.07

Belongings

Paper Pal

2025.03.05

Belongings

Ako Dantsu

2025.02.07