Artisan

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photos: Keisuke Fukamizu

2022.06.15

Introducing the tonkori, the sole traditional string instrument of the Ainu people, whose indigenous population, from the seventeenth into the nineteenth century, spread north from Tohoku and Hokkaido into Sakhalin (known in Japan as Karafuto) and the Kuril Islands. Forgotten by modernization, and faced with extinction, this haunting instrument is ripe for a revival and has no bigger advocate than Shigehiro Takano, a woodcarver who builds tonkori in the Nibutani district of Hokkaido. We paid a visit to his studio.

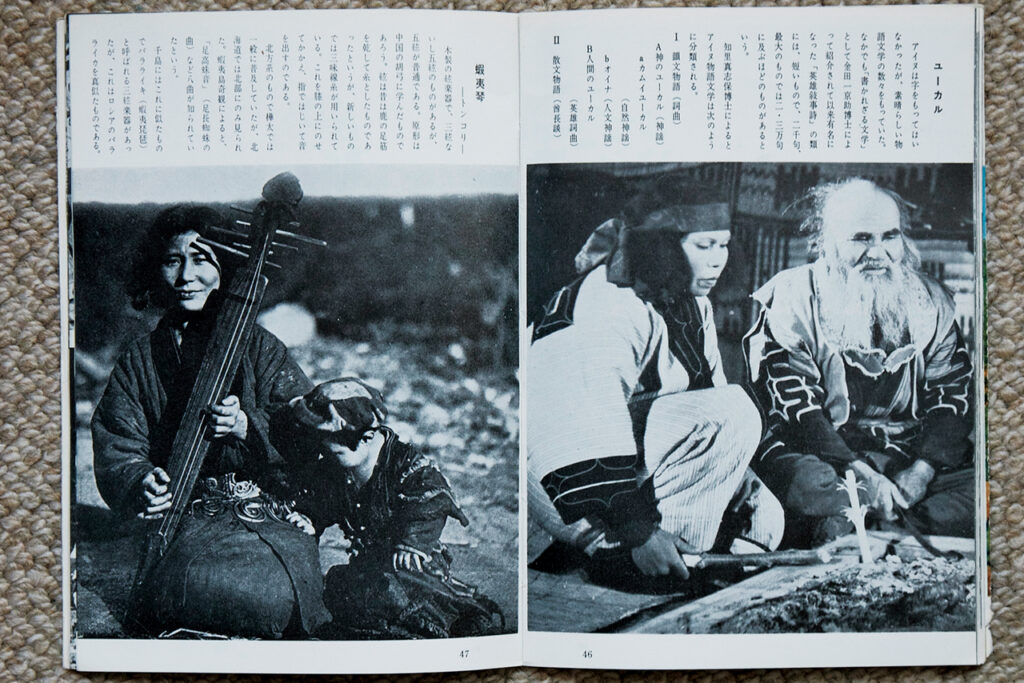

“Tunkun,”“dongri,”“tangara,”“tokari”… With various names given to it throughout ancient history and generally referred to as the “tonkori” in modern times, this instrument is the only Ainu stringed instrument (commonly referred to as ka, or“string,”in Hokkaido) that has been passed down for generations in parts of southern Sakhalin and towns such as Souya, Monbetsu, and Shari in northern Hokkaido.

The boat-shaped instrument, whose body is made by carving out a log and attaching a thin sound soundboard, it generally has five strings and is played with your fingers. The strings are all played “open” so its playing style is more similar to a harp than to a guitar. In ancient times, Japanese red pine was used to make the body, while vegetable fibers of nettle plants and twisted tendons of native Hokkaido deer were used to make the strings.

The roots of tonkori can be traced back to the Eurasian continent where it originated, but its actual history has not been confirmed to date. When reading historic literature containing references to tonkori in ancient Japan, there is mention of Shibue Chohaku, a Shogunate medical officer during the latter part of the Edo period attending a show where the tonkori was played in 1799 during his search for Ezo, the area known today as Hokkaido. He depicted the shape of the tonkori and individual steps on how to play the instrument in his personal manuscript, titled “Ezo-jin Dankin-zu.”

Inside “Ezo Manga,” a book that depicted the Ainu lifestyle in drawings written by Takeshiro Matsuura, an explorer during late Edo period (also the originator of the name “Hokkaido”) who made six expeditions to the Ezo region during his lifetime, there is an image of an Ainu man playing the tonkori. It is also recorded that Takeshiro presented the Lord of Mito with his precious tonkori that he obtained during his time in Sakhalin.

The Ainu people played the tonkori during celebratory occasions in their everyday life, and also believed that the tone produced by the instrument possessed magical powers. The tonkori’s shape is traditionally said to resemble a woman’s body, and the rest of the instrument is given corresponding body part names such as “head,” “neck,” “shoulders,” “torso,” and “feet.” In the middle of the torso there is a hole called the “peso” or “hankapuy,” and a pebble is placed within the body cavity of the instrument, granting it a “soul” (ramatohu). Leaving a tonkori unattended was said to have evoked evil spirits. The tonkori was also used for ritualistic purposes such as when there was a plague, where shamans would play the instrument over several days to protect the people from evil, and during festivals and other rituals involving music and dancing.

The existence of the tonkori, which had been part of Ainu culture for many generations, gradually began to fade away amid the modernization of lifestyles following the Meiji Restoration. During the Showa period, along with the passing of elder musicians, ancient tonkoris were stored as part of a collection in museums and neglected in modern history. A handful of people, such as Sakhalin-born Ume Nishihira, who was a major contributor to the preservation of Ainu culture, continued to play the tonkori until her death in 1977. In succession, fellow traditional Japanese musician Tomoko Tomita became the last remaining performer to have received official lessons from an authentic Sakhalin Ainu tribesman.

However, in the 1990s, when the tradition faced extinction, the number of people who studied the art of tonkori as part of greater Ainu cultural restoration effort slowly began increasing. Musician OKI, leader of the band, “OKI DUB AINU BAND”, even created an original style of music by combining elements of traditional Ainu sounds with modern genres such as dubstep and rock n’ roll. The tonkori became widespread in mainstream media thanks to their music, and the population of tonkori players is slowly but surely increasing in recent years.

Shigehiro Takano, wood engraver and owner of “Takano Mingei” at Nibutani in the town of Biratori, Saru District in Hokkaido, is the last remaining person left in the region who possesses the skills to craft a tonkori. Born and raised in Tokyo, Takano first arrived in Nibutani during a summer hitchhiking trip at the age of 22. He became attracted to traditional Ainu wood sculpturing after working part-time under master craftsman Moriyuki Kaisawa and became his official apprentice. Kaisawa passed away several years later, and Takano set up his own business in 1979. For over 35 years, he and his wife Keiko have continued to create traditional Japanese instruments.

Unique patterns are depicted on all everyday Ainu tools such as ita (trays), nima (bowls), makiri (knives), and iku-pasuy (ceremonial sticks). Engravers combine a series of Ainu patterns such as “Moreu,” “Aiushi,” and “Sik” to create their own unique designs.

During a time when only mass-produced wooden engraved bear models were popular among tourists as souvenirs and everyday crafts originally used by the Ainu people were no longer being produced, Takano created a policy of specializing in traditional folk art.

The “Nibutani Ita,” a flat and rounded half-moon shaped tray that has been passed down for over a hundred years in the Sarugawa River basin region, is one of the most popular items. The trays feature detailed fish-scale design carvings, called “Ramuramunoka,” which require an extremely high level of concentration and advanced techniques to create.

In the words of Takano, “I insert a soul into each individual carving.” The tonkori manufacturing process involves placing a glass bead through the peso (hole), which represents giving the instrument a soul. The soft spiritual sounds made by the tonkori have the ability to ease the mind and soul. The spiritual background behind the tonkori gives us a glimpse of the bigger picture of the lifestyles of the traditional Ainu people.(Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 1)

Traditional Ainu Folkcraft Ita made by Shigehiro Takano are available for purchase on our official web store.

Artisan

Fe Ca Sn

2025.07.02

Artisan

WaNa

2025.06.18

Artisan

Aiko Hama “M e m / o / r a n / d u m”

2025.05.21

Artisan

Cécilia Andrews

2025.05.07