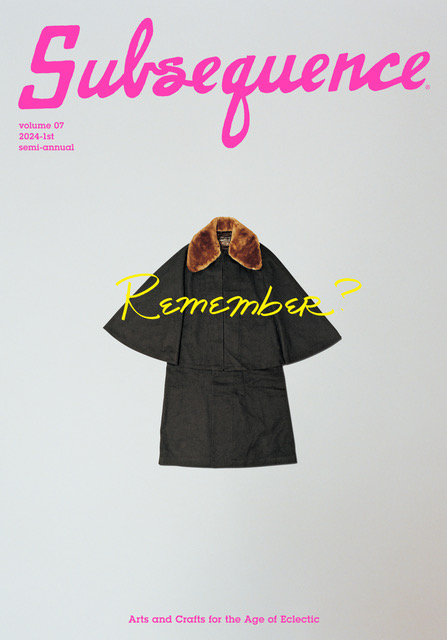

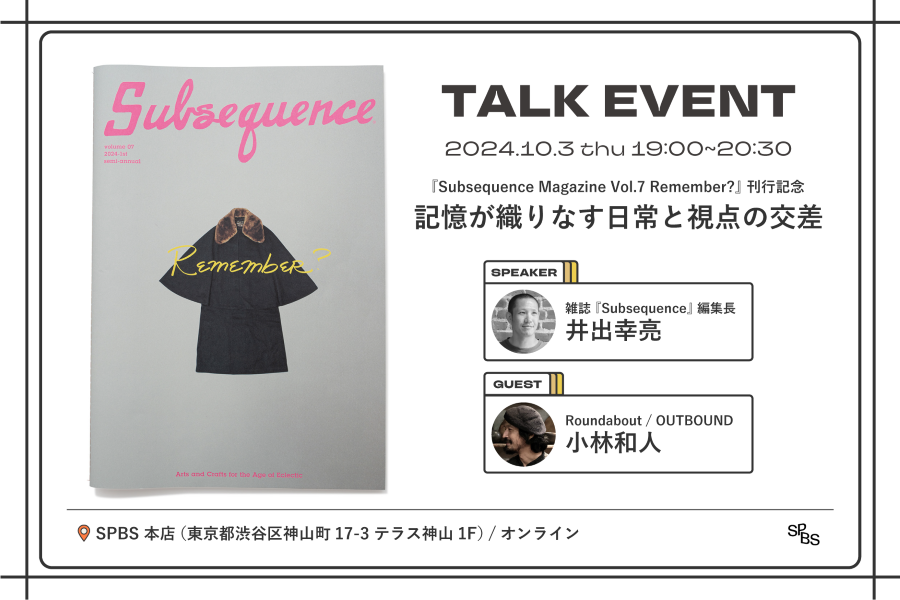

Event

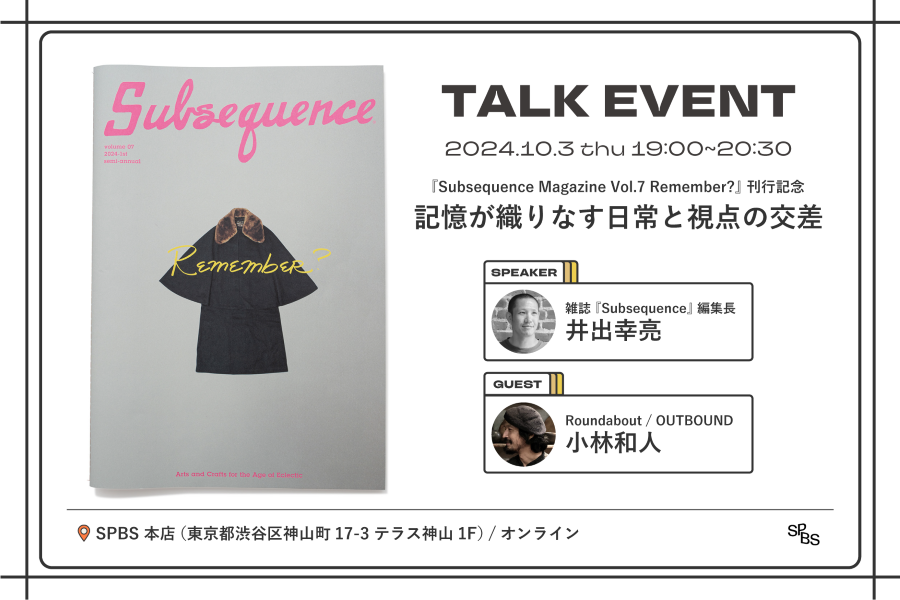

Talk Event: The intersection of everyday life and perspective woven by memories

@Shibuya Publishing & Booksellers

2024.09.20

Event

Subsequence

2023.02.21

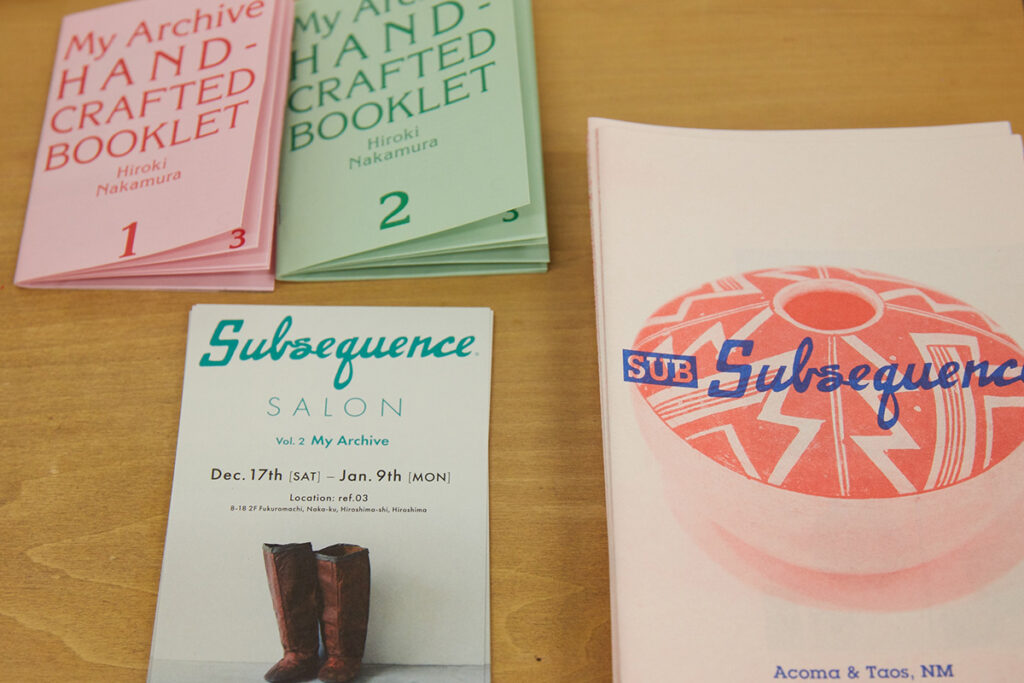

“Subsequence SALON vol. 2 My Archive” was an exhibition event put on by Subsequence Magazine and hosted by ref. 03 in Hiroshima at the end of last year. We disclose the contents of the special talk show event held for the opening featuring Hiroki Nakamura, Creative Director of visvim and Kosuke Ide, Editor in Chief of Subsequence.

IDE: Thank you for joining us today. My name is Ide, Editor in Chief of Subsequence. It’s a pleasure to see everyone here today. For this “My Archive” exhibition we have gathered a portion of Mr. Nakamura’s collection of archival objects to be showcased. Originally, I was the writer in charge of Mr. Nakamura’s serialization titled “My Archive” that was a part of POPEYE Magazine from 2012 to 2018. There was also a book published in 2018 that was a collection of the articles that had released to date.

FURUHATA(Subsequence Producer): You could say it was the activities related to such publications that led to the founding of the magazine Subsequence by Cubism in 2019.

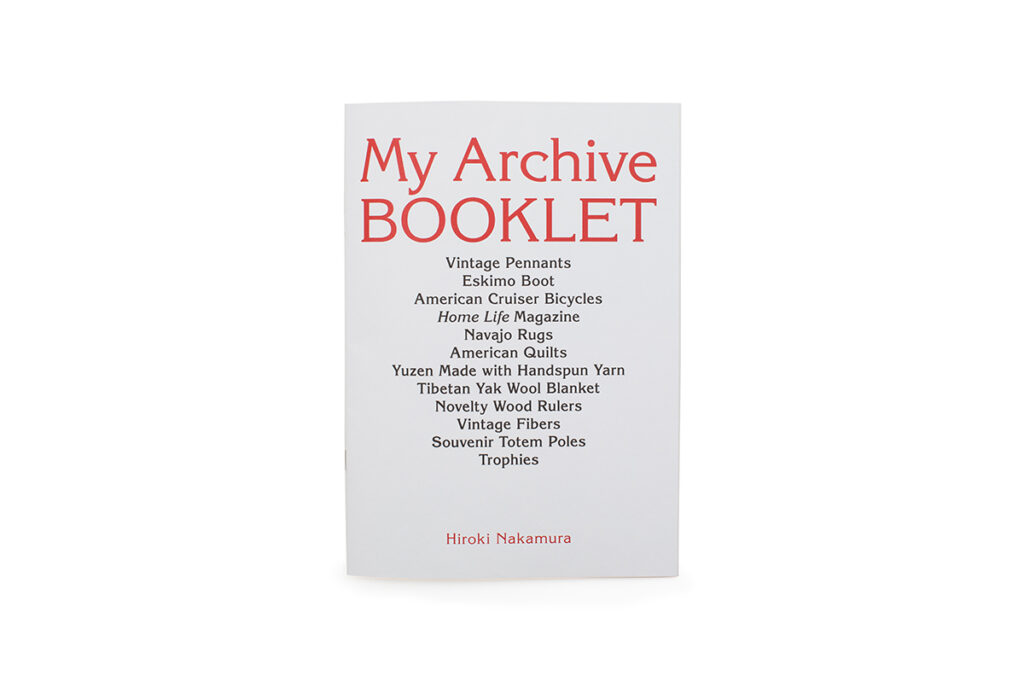

IDE: That’s correct. So, when the “My Archive” book was published there were actually a dozen or so articles from the serialization that never got released. Some of these unreleased articles were made into a mini-booklet and included as an appendix of Subsequence vol. 5 which was published earlier this year. In conjunction with this exhibition event the remaining unreleased articles were revised and collected for a zine we published, called the My Archive Booklet. I hope you will take a look at the actual zine a bit later.

During the interviews for the original serialization Mr. Nakamura would bring a variety of personal items every time and talk about what he felt from these things and also share additional memories he associates with each item, I was always amazed as each piece he would bring spanned a wide range in both era and regions of origin throughout the world, they were truly diverse in nature. Typically, most collectors tend to focus on specific genres or brands, where the intent to collect is consistent and easier to understand as it is more common for these types to limit the range of such collections by their own accord, however in Mr. Nakamura’s case there is no easy way to describe or categorize his collecting habits with words. That is why I was so interested in learning more about his perspectives when collecting things. Further details can be discovered and understood from reading this book, “My Archive” so it would be a great joy for me if everyone here would take the time to have a look at the book for themselves. Today I would like to ask Mr. Nakamura a variety of things including how he became interested in such things, what does he usually look out for and how does he think, as well as what does he think when collecting.

NAKAMURA: Hello everybody, my name is Nakamura. Thank you again for coming today. On most days I work as Creative Director for the brands visvim and WMV. I first became interested in these kinds of old things when I was younger in my teenage years. I grew up in the 1980’s when there was a movement for collecting vintage clothes, back then the attraction was simply, “That’s cool, I want it…”, however once I started to make things myself, I became more interested about the reasons and had thoughts like, “What is it about this thing that I am attracted to? What is it that makes me think this thing is good?” I then started collecting things that would get caught in my so-called filter. My gatherings included textiles, bicycles, and even getas; I continued to collect things while simultaneously training and honing my filter.

IDE: Whenever I listen to Mr. Nakamura speak it’s always impressive and like you mentioned just now, you are conscious of this “filter” you describe that is directed by your own point of view. First there are all these things that you have chosen through your filter and then afterwards you think about why you chose them; this is your process. This is such a valuable process; however, I’ve been thinking though that this kind of conscious process seems to be getting forgotten. May I ask you a little more about that?

NAKAMURA: When I design products or do such work, I think a lot about the differences between thinking and feeling. They are completely different things, but in normal everyday life I don’t think they are consciously distinguished. For example, when you describe a thing in a way like, “this was designed by so and so,” or “this thing is from which time period,” I believe these kinds of thoughts can be considered as thinking. On the other hand, feeling is more about being attracted or liking without thinking, or something more like being impressed. I personally want to cherish those sentiments more. For instance, when I go to an antique market, I try to focus on what I feel rather than listening too much to the explanation of a product being given by the shopkeeper. The explanation is merely information. First, I look for things that get caught in my sensory filter, then after that, I analyze and think about what attracted me to it. I feel with my right brain and think on it with my left brain, sort of like playing catch from left to right. I feel it’s important to keep those things in mind as I conduct my work.

IDE: It’s like inherently knowing it’s nice before thinking about it, or like when you reach for a thing without much thought…it’s an innate attraction at first, that is followed by time to think about why you thought it’s nice. Is it safe to assume though that as you repeated this process you discovered some common thread among all the collected things.

NAKAMURA: I think so. I have assumptions as to why like, “oh, I must be drawn to this thing because this thing is a certain way,” or by picking things up in my hands and analyzing certain focal points as if to investigate further. This kind of action is really important to me as part of my creative process.

IDE: This process you speak of Mr. Nakamura, requires a kind of daily training like practice does it not. I assume that you yourself come into contact with these things daily, which hones your senses and keeps them active. If you remember we had a special article in Subsequence vol.5 where several of us from the team along with you went to the antique market in Kyoto together. As per your suggestion we went to the antique market at the Toji temple to go search for things and bring back our finds to talk about those things.

NAKAMURA: Didn’t you think that was such a fun thing to do as part of our jobs (laughing). We each had a budget of 20,000 yen didn’t we?

IDE: It truly was! (laughing). Would you tell us why you suggested doing such an exercise, and what the act of going to an antique market means to you?

NAKAMURA: During a previous conversation I was having with you Mr. Ide, we spoke on wanting to inform everyone about the difference between thinking and feeling. I think in our everyday lives we don’t really think about such things much. Even if we think something is nice, we don’t think too deeply about why we felt it was nice. That kind of thing is hard to do unless you do it consciously and with such intent. It’s even challenging for me, so I think it’s important to always be trying. I suggested going to the antique market as a training exercise to think about such things.

IDE: It is true that antique markets are just rows of things with limited information. You can only really ask the shop keepers. Since information is limited, you have to make decisions with your own eyes. There are many stores that don’t even have prices on things and every time you ask the shop keeper the prices keep changing (laughing). Or you try and bargain with the shop keeper to get it cheaper. These kinds of interactions are very different from the general shopping environment of today. For instance, if you buy something on the internet, product specifications and relevant information is all there, and you can also compare prices between different stores. In the antique market though you can’t do any of that. Almost everything is one of a kind so there is no comparing. In that sense it’s great training for what we are talking about.

NAKAMURA: You have to come face to face with your senses. The shop keeper could tell you, “This is from this time period and from this specific place,” but you don’t really know if it’s true. That’s why it’s most important to know how you felt and what you think is special about something. In America, if there is an antique mall or something of that nature, I go to have a look even if I’m not planning to buy anything. I get inspired and it’s good training. These sorts of conversations are what led to the idea of the “My Archive” exhibition this time around.

IDE: Through this training of yours I sense there is one common trait in the things you select Mr. Nakamura, and that is handmade things. Why are you attracted to such things and how do you feel about it yourself?

NAKAMURA: Well, take for example the Indian baby blanket over there. The graphic details are expressed with a sashiko embroidery, carefully sewn one stitch at a time by mothers and families for their babies. I am able to sense and feel the love they have for their children when I think about this thing.

IDE: Do you mean to say that a person’s feelings or emotions are expressed more apparently during the process of making when that thing is made by hand?

NAKAMURA: I definitely think so. For example, if someone is sashiko quilting by hand no matter how much they try to sew uniformly, people’s moods have “waves” from time to time right? With those fluctuations, something representing that person’s human nature is revealed. It’s clear that the outcome should be different in comparison to something sewn with machinery like a sewing machine. In this context I believe it’s really important to understand “what the maker thinks” and as a result when I make things myself, I pay close attention to that sort of thing within my process of work. As we were speaking about earlier when you take in too much “information” it could cloud your output. Even if the customer has no direct knowledge of such matters, I’m sure it is something that they can feel. I think it’s important to control the information you take in, including for example what movies and books you see and don’t see.

IDE: This kind of baby blanket and things similar to it are different from what is considered to be “merchandise” right. It was made specially with the intent for their children to use or to use themselves. I feel like with this sort of thing an even more private feeling is revealed when it’s created.

NAKAMURA: I agree. Of course, I make products within the context of a company that is intended to be sold commercially so there is absolutely no way I can compete with a blanket that a mother or grandmother made for their children, however that is exactly why I try to think about how users can enjoy our product longer, and I would like to infuse my own positive message into my work. I believe then that even merchandise can begin to reveal an attraction as people use and wear our product more. As I continued collecting such things and passed them through the filter of “time” I felt everything I had started to shed much of the unnecessary surface elements to reveal something that can be considered its true essence; I’ve definitely started thinking a lot more about that.

IDE: With that being said, it is apparent that a lot of the things that are here are from the past, and many of the things are old, however Mr. Nakamura it’s not that you only have an attraction for rare old things, is it?

NAKAMURA: That’s exactly right. It’s not that “things are good because they’re old.” That would be the thinking with the left brain. Especially within the modern commercial world we are living in there is an overflow of things that are appealing to the left brain, so my hope is to make things that aren’t like that but rather have a natural power that appeals to the senses which transcends any kind of reasoning.

IDE: By the way, a little while ago something you spoke about with me was very intriguing, it was about things made during the Edo period, after the opening of the country, and things made after the Meiji period; especially things made after the beginning of the 20th century and how the impressions you get from the things of each era were greatly different. Today, as you have actually brought some things for us, I was hoping we could ask you further on what kinds of differences you see.

NAKAMURA: Yes, this is a very powerful piece, a kimono presumably from the early Edo period, which is made of a shibori style Yuzen dyed silk fabric with hand embroidery detail. While I usually live in America, I have the opportunity to work with many workshops all over Japan on a variety of projects, however when I try to emulate this piece from this past era today I’m often told that they’re unable to. Then I wonder, what do they mean, “they’re unable to.” After all this time, where the techniques should have evolved, why?

IDE: Why aren’t they able to?

NAKAMURA: I think it is because between then and now, the silkworm itself, which is the material has changed and the definition of working hours is also different. However, I think the biggest difference in these modern times is the feeling. It’s a difference in sensibility or world view. I’m not completely sure as I am no historian, but the “right side of the brain” that we talked about earlier, I have been thinking more and believe lately that there was an era where that ability to sense things was used more fully by humans. The small world map near the entrance of this venue, is from the 3rd year of the Kaei era, which is 1850. Similar to the shape of this map, the “world view” of the people from that time compared to people today was different, and lately I think the prior perspective was something closer to nature in a sensory manner.

IDE: I think I know what you mean, soon after this map was created the country opened its borders and they started making maps that were more scientific so to say and the maps themselves were more accurate to scale. The versions prior to that are maps with rougher shapes and uneven lines. The way Japan is depicted is huge as well.

NAKAMURA: Yes, if the world view is different, the sense of distance from nature is also different. Maybe that was why they were able to make something like this (Kimono from the Edo period). I feel like that is why they had ideas for such bold patterns, this feeling and sensibility which differed from modern people contributed to that. That is when I thought, you know the garden I had Master Yasumoro create for visvim in our Naka-Meguro store.

IDE: You’re speaking of Mr. Sadao Yasumoro, master gardener who is over 80 years old.

NAKAMURA: I felt that the feeling the master creates his garden with was very close to the bold sense of the people who were making things in the Edo period. Every day he would knead the earthen walls by hand. He would touch the soil, touch the stone, and then crush the stone, this life of his is very close to nature. I started to wonder if there was a hint there.

IDE: Subsequence vol.3 features a long interview piece with Sadao Yasumoro, it would be great for everyone to see it to have more context. I recollect Mr. Yasumoro saying that he has no detailed estimates or does not prepare a detailed plan when creating his gardens.

NAKAMURA: He has an ideal image in his head and then he proceeds to take this bold image and creates everything by hand. He will pick up some driftwood from the river and uses it to build earthen walls. It all started with the garden at my home in Tokyo, I was gazing upon it one time and noticed the pillars of the earthen walls were crooked, and the tree used for the gate was split in two, I became so curious about the design and looked into it and discovered it was Master Yasumoro who had created the garden, this was how we met. I asked Master Yasumoro, “Where do you go to buy such wood?” His answer was, “Well, you actually go to the river to pick up wood like this.” He picks up all his material in the mountains and riverbeds to make the earthen walls and everything else. I thought it was so amazing.

IDE: A garden cannot be made according to a blueprint like an architectural project. For example, you cannot plan with a blueprint how to stack natural stones as it can really only be done by stacking them one by one with your hands. I don’t think it’s possible to create those kinds of gardens unless you open up your senses by actually feeling and touching the soil and stones, which is something that cannot be provided by information. There is definitely a sense of improvisation in his method of creating.

NAKAMURA: When I saw the way Master Yasumoro conducted his work, I thought to myself, “Oh, even today there are people with that sensibility,” I was moved and at the same time I thought that today’s world is considered to be much more convenient than it was in the Edo period where the exchange of information has become faster and easier, but in reality our ability to sense and feel has been degenerating. When I see Master Yasumoro though, I felt like there was some sort of hint there. Maybe it is still possible today for me and all of us to still tap into this potential. In fact, only a mere hundred years ago we still had that sense and feel. I do feel though that this sensibility or feeling that I’m describing does not reveal itself unless you’re closer to nature. For example, if you place an insect or animal into a plastic box for a prolonged period of time, it will become weak. As they grow weak, I’m certain their senses and vitality will start to disappear as well. When I thought of this as a hint, it gave me much hope. I can become like Mr. Yasumoro, everyone can be more like him, when that happened, I felt there was some hope for the future of Japan. I just think you have to take notice of this fact. There seems to just be a lot of negative news these days, and the world seems to be moving along that vector, but I thought, “Wait a minute.” Then I thought further, “It was possible to make this (Edo period kimono), so it has to be possible to make it today as well,” and I was able to become a bit more positive.

IDE: You had mentioned before that especially in Japan this type of person who possesses this sensibility and feeling, including craftspeople similar to Mr. Yasumoro is still around but becoming fewer and fewer. I think you may have much more clarity on this situation where you are able to notice it better since you have lived abroad in America for a while now.

NAKAMURA: I do feel that way. Fundamentally I don’t think making things is possible unless one has high morals. For example, if the maker thinks, “Nobody is looking, so this is good enough,” they are only able to make things of that quality and level. However, on the other hand if they work while thinking, “I want to raise the level of quality, and make it even better,” it becomes better and better. This sort of “dignity” exists in the culture of Japanese craftspeople. The finished product gets better because of a feeling which comes from their pride to want to improve the quality of their work, and not because someone is watching over them or how much money they can make from it. We have the great opportunity to work with people that have such intentions and as a result are able to make great things within the context of Japanese production. It’s really important and something of great value. So, I say to Master Yasumoro and other craftspeople that they are truly a treasure.

IDE: That is so true. On the other hand, to speak conversely, the reality of the situation is that this kind of thing is barely hanging on and being lost day by day, isn’t it?

NAKAMURA: That is the truth. Every season I receive word that this workshop in this production area is going out of business, this kind of thing is happening frequently. But it was possible to make this (Edo period kimono) then, so it’s possible now. It was possible in the past.

IDE: That is if we can regain the feeling and sensibility from that time.

NAKAMURA: Yes, that culture is still alive in Japan, so we need to cherish it. For example, in Japan there is a culture of kimono’s and there are still workshops with craftspeople, but if these kimonos lose its place as a tool or part of everyday life and become completely costume garments then it becomes challenging to continue the tradition. To preserve and ingrain it again as a part of everyday life. I believe that is my job as a designer.

IDE: It is not as important to simply keep making and preserving a thing that appears the same in a superficial sense or the same outward appearance, but rather more important to figure out how to keep and maintain the feelings and sensibilities behind it. So, the intent when you make products is to not just recreate and duplicate something old or vintage, the purpose is not to make something in the same shape or form, but to explore the meaning or background of things and revive or adapt them to the modern living environment. I get a sense of your positive attitude and belief that even now it should be possible.

NAKAMURA: When I see someone like Master Yasumoro, I believe it’s still possible for us to return to that feeling. Not just myself, but if everyone can gain a sense of this feeling, I’m sure the world will be a wonderful place, don’t you think?

Photo: Keisuke Fukamizu

More Stories

Hiroki Nakamura Interview for the “My Archive” exhibition

The work of Master Gardener Sadao Yasumoro

Event

Talk Event: The intersection of everyday life and perspective woven by memories

@Shibuya Publishing & Booksellers

2024.09.20

Event

Talk Event Announcement

2024.09.19

Event

Subsequence Salon vol.4 Special Giveaway

2024.09.05

Event

Subsequence Salon vol.4

Samuel and Stephen's Works

2024.09.04