Eclectic

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photo: Hiroki Nakamura, Aya Muto

2025.02.21

Sunlight pours through the big glass walls of the expansive living room. A private pool off the patio. A single story, with an overhanging flat roof…these days, the phrase “California Modern Living” evokes a classic landscape known to all.

Born in the mid century period of the 1940s-1960s, this approach to residential design has become a fixture of the visual landscape of the region, but it’s fascinating to note it was created and developed by two architects from Austria. If Rudolf M. Schindler and Richard J. Neutra had not left Europe for America, what we now know as California Modern Living might have taken on a very different shape.

Both Schindler and Neutra, who met at the Vienna College of Technology in 1911, were greatly influenced by Adolf Loos, a pioneer of modern architecture who had lectured at their university and is famous for exposing Viennese hypocrisy in his f lamboyant essay, “Ornament and Crime.” They also admired the work of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Europe at the time was experiencing the sudden rise of modernist architecture, a practical and functional approach to buildings that sought to transcend personal and regional particularities. Favoring a rectilinear geometry that abandoned traditional elements of design and ornamentation and utilizing materials from industrial production (steel, concrete, glass) to construct spacious interiors, this ethos was promoted by, among others, the German architect Walter Gropius and the French architect Le Corbusier, giving rise to the “International Style.”

Riding the wave, Schindler felt himself drawn to the new continent and relocated to America in 1914, obtaining a long sought position in Wright’s office three years later. After studying under Wright, he established his own practice in 1922, building a home and studio on Kings Road in Los Angeles. Details like the capacious wood and glass walls of the courtyard, which faces away from the street, and the organic transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces create a link with nature that shows the influence of Wright.

Nine years after Schindler, Neutra left for America in 1923 and spent four months working under Wright at the great architect’s studio, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Thereafter, Neutra relocated to Los Angeles and reconnected with the more experienced Schindler, completing the Lovell Health House in 1929.

Situated on a steep hillside overlooking a canyon view, this three-story steel-framed structure sports a large flat roof, structural columns and a pool. The daring design surpassed the modern architecture coming out of Europe, boasting not only a fresh design but a progressive use of industrial materials on a difficult site.

In 1932, Neutra built the family home that also housed guests and a growing architectural practice, the VDL Research House in Silver Lake. The glass-walled penthouse on the third floor, soaking up the sun, and the patio surrounded by greenery strove for a balance with the unique natural landscape of Southern California.

Neutra, whose development of home designs like these arguably makes him the forerunner of California Modern Living, came into his own in the years after World War II, an age of industrialization. Active through the 1960s, the golden age of his career, he designed a large number of buildings in the region.

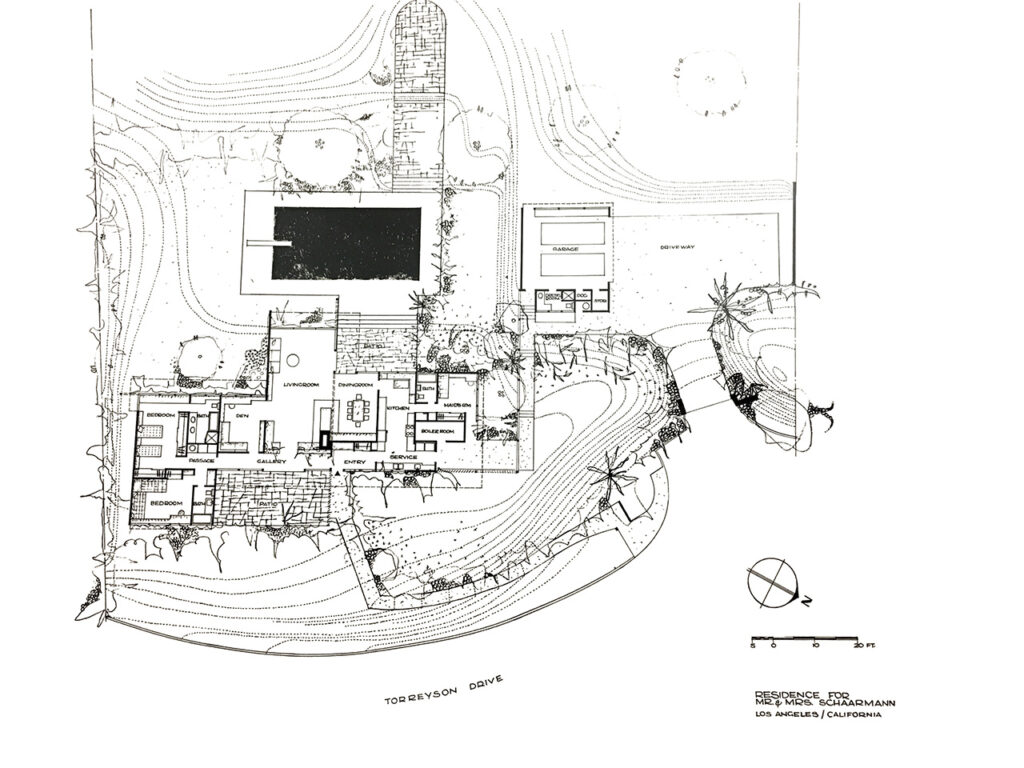

Several homes by Neutra from this period have survived to the present, but few in their original form, due to renovations made by a succession of owners. One such example is the Schaarmann House, designed by Neutra in 1951, which stands in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles. Located off Mulholland Drive, with a view of Laurel Canyon from the pool, the residence was modified extensively by two generations of owners.

“In 2016, when I heard the last owner of the Schaarmann House had let go of the property, I started to imagine what the house must have looked like in its original state, as Neutra intended,” says Hiroki Nakamura, creative director at visvim. After years of living in Los Angeles, Nakamura had developed an enduring fascination with the mid-century architecture that blossomed from the area.

“California’s modern architecture, epitomized by Schindler and Neutra, somehow reminds me of traditional Japanese homes, especially the ‘post and beam’ construction and the open spaces, seamlessly connecting indoor and outdoor areas. Perhaps this is the influence of Wright, who had a deep connection with Japan. These architects came over from Europe, studied under an American architect who had worked in Japan, and created a style unique to California. I’m interested in this process where diverse cultures mix together and something new is born. It reminds me of my own day-to-day work, where I’m influenced by cultures from all over the world.”

Known also as a collector, Nakamura has drawn inspiration from vintage items across history and the globe, as a starting point for unique new products. In his words, “learning about an item’s original form, from when it was made” is the most important thing about this work.

“Whenever something grabs me by the heart, I’m always curious to know the secret of what makes me feel that way. That’s why I consider it essential to understand the thoughts and feelings of the person behind the creation. But once the materials and form of something have been altered by someone else’s modifications, the original concept starts to fade. I like to strip the paint off bikes and motorcycles and swap in authentic parts, restoring them to original condition, but in this case, I thought I’d try the same thing with a house. By dialing back any renovations to as close to the original design as possible, I hoped I could unlock the message that Neutra had embedded in the building at the time of its unveiling in 1951.”

With this in mind, Nakamura launched the “Schaarmann House Restoration Project.” Under the guidance of architect Gina Gilbert Moffitt of the firm Kiyohara Moffitt, and with advice from Dr. Barbara Lamprecht, architectural historian and Neutra scholar at UCLA, restoration of the building was soon underway.

The first thing Lamprecht and Moffitt needed to determine was which parts of the house had been modified and how. “The prior owner passed along the original blueprints,” Moffitt explained, “but diagrams alone won’t tell you about incidental materials or the original finishes. As a result, I spent many hours in the archives at the UCLA library, which had been gifted all of Neutra’s files.”

The archives Moffitt mentions have a file box devoted to the Schaarmann House, in which she found the complete correspondence between Neutra and his clients, the first owners of the house, discussing every aspect of design and construction.

“Neutra left sketches and freehand notes in the margins,” Moffit said. “I also came across the correspondence between Neutra and the foreman. Through these documents, we were able to retrace the process Neutra used to realize his design.”

By auditing the building, the team could assess not only major changes like the expansion of the footprint, the extension of the living room and kitchen, and the addition of the office, but also more than sixty years of minor changes, everything from interior and exterior wall and floor materials and built-in furniture down to the finish of the surfaces.

Moffitt explained some of the many changes they discovered.

“The cabinets had been redone, and the doorways heightened for the owner, who was very tall. The bathrooms and kitchen had been remodeled, and later on an air conditioning system had been installed, putting a massive air duct through the roof, topped off with an ugly piece of machinery. There were also big, unsightly electrical boxes for powering the exterior window shades. All the ceilings and the beams—along with nearly every wooden surface of the house, including Neutra’s classic ‘spider legs’—had been painted yellow.”

Black and white photos of the Schaarmann House at the time of its completion only show the living room and dining room, along with some exterior views, but by zooming in to the extreme, they picked up traces of additional details. The next problem to solve, after pinpointing these little touches, was how to restore those details that were lost to renovation.

“When people restore mid-century homes, they almost always opt for new, modern materials,” said Moffitt. “This usually means brand-new fixtures and appliances, especially in the bathrooms and the kitchen. But Nakamura wanted to use the same f ixtures that were put into the house when it was built. Through our research, we identified the original manufacturers and sourced almost everything from salvage dealers who had deadstock.”

The process of restoring modified details continued. The missing built-in cabinets were reconstructed using techniques outlined in the original millwork as specified in the shop drawings from the 1950s. Since the ceilings that were painted over were redwood, which is a soft wood, sandblasting was not an option, making it necessary to strip the paint using chemicals and sand the wood by hand.

“The wood panels of ceilings are all tongue and groove. Neutra’s simple designs used materials that were inexpensive at the time, but making them look elegant requires fairly complex methods. The plywood of the wall panels and cabinets was laid out with incredible precision, so that details like wood grain and how the wood is cut must not be overlooked. In that sense, the restoration process was a fascinating window into Neutra’s mind,” said Moffitt.

Lamprecht underscored how every single detail was imbued with Neutra’s architectural philosophy.

“In later years the patio was retrofitted with brick, but originally it was paved with the same flag stones as the living room. The inside and out were separated by a big sliding window, but this too had been removed in later years. Now that things have been restored, I think I understand why Neutra found it so important to be able to penetrate the boundary between inside and out, forming a link. In the 1950s in particular, Neutra’s homes had an open format, characterized by a union with the natural landscape. His designs eliminated the need for hardware on the cabinets. Neutra believed that housewives should be able to spend their time on more important things than chores like polishing the cabinet knobs. At the same time, this creates a beautiful plane, free from visual obstructions. His thinking is apparent in every detail, from the weave of the cushions to the piping of the sofa, everything coming together to give us Neutra’s architecture.”

Every detail has meaning, a dialogue that forms a single system of design. Change one thing, and you disrupt the balance of the whole. Hence why Nakamura was so adamant about returning everything to as close to original condition as possible.

“Hiroki and his wife Kelsi chose Formica for the kitchen counters!” Lamprecht recalled in disbelief. “With all the different options available today—granite, Caesarstone, marble, stainless— they brought in Formica, which was a progressive product at the time. Do you realize how radical a choice that was? I see this as a contribution to restoring the humility of the house. Luxury isn’t about premium materials or grand size, but the details that make a home more comfortable for the family who lives there. Almost no one ever makes a building smaller, especially in Los Angeles, so the fact that Hiroki chose to scrap the additions even if it meant having a smaller space is really something special. This house is a prime example from what we call ‘Neutra’s golden age,’ and in my view, the true spirit of the home has been revived.”(Reprinted from Subsequence vol.3)

Eclectic

〈vol.8〉Content of this issue: “Favorite Items” visvim WMV Fall and Winter 2025

2025.12.12

Eclectic

〈vol.8〉Content of this issue: Preserving Homes in New York: The Fluxus Dream of an Artists’ Co-op

2025.12.09

Eclectic

Subsequence Magazine vol.8 “A Sense of Something” Issue

Releasing on 13th December ‘25

2025.12.03

Eclectic

Vol.8 “A Sense of Something” Issue

Releasing on December 13, 2025 (SAT)

2025.11.27

volume 08

2025-1st

Bilingual Japanese and English

260 × 372mm 148P

Release date: December 13, 2025