Eclectic

text: Kosuke Ide (Editor in Chief)

photography: Keisuke Fukamizu

2021.09.28

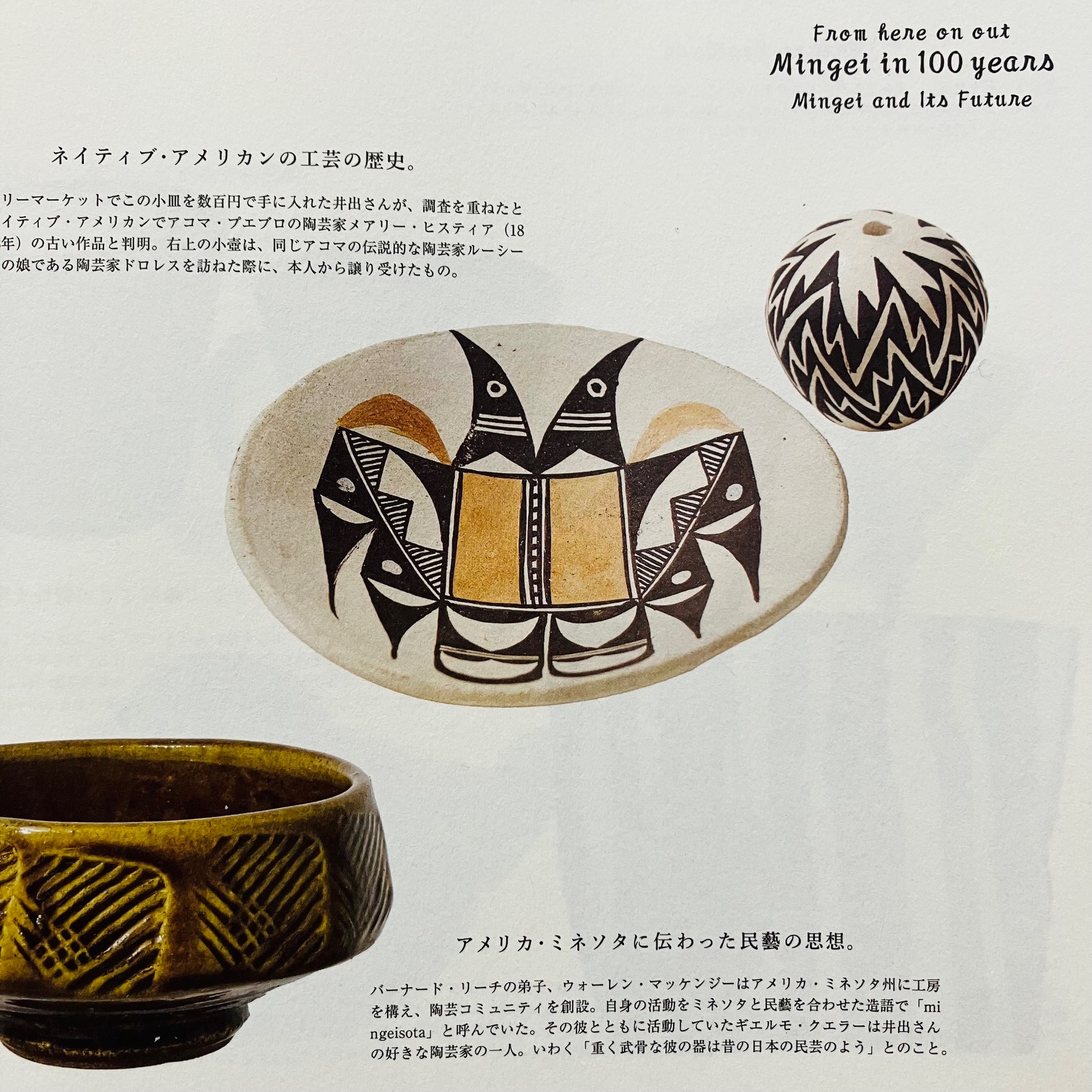

The history of the people who preserved and passed down the traditional lifestyle cultures of Korea.

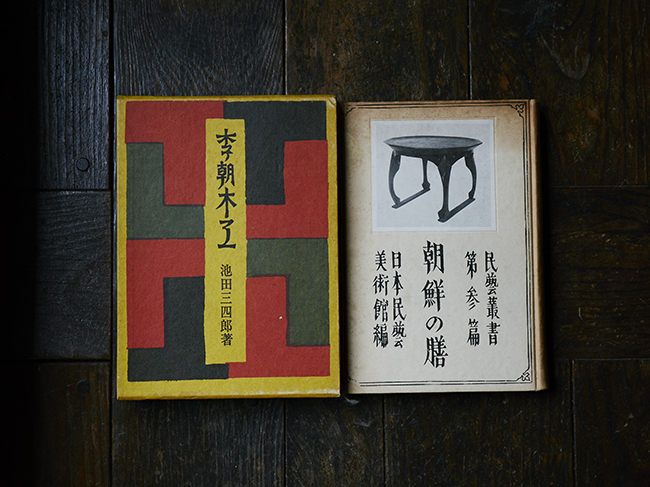

In Japan, the name “Richo” has long had a special connotation for people who love antiques. The “Richo Dynasty” is the popular name in Japan for the “Joseon Dynasty,” a Korean dynastic kingdom led by Yi Seong-gye that lasted for approximately five centuries, from the early 14th century until the annexation of Korea in 1910.

Traditional crafts such as porcelain and furniture created in this era have always been held in high regard, and still demand a high value today.

Crafts from the Richo Dynasty continue to mesmerize connoisseurs for one main reason: their “simplicity.” While the crafts from the Koryo Dynasty, which preceded the Richo Dynasty, featured elegant styles with intricate details created through advanced techniques, the crafts from the Richo Dynasty were generally simple and unadorned, with no fixed shapes or color tones, and sometimes had a “rough” finish. The shift in Korea from Buddhism to Confucianism is believed to be one of the reasons for this change of styles. In the teachings of Confucianism, one of the core values is the importance of being “honest” (having a pure heart with no selfish desires), and thus it was looked down upon to be extravagant and flashy. Joseon white porcelain, which was made without the use of any flamboyant enamels, is thought to symbolize the religious values of that era.

Among the many crafts from the Richo Dynasty, the tea bowl was treasured as a perfect complement to the aesthetic of simplicity and elegance of “wabi-cha,” a style of Japanese tea ceremony founded by Murata Juko, a tea master and monk active in the middle Muromachi period, and later popularized by Sen no Rikyu.

During an era when luxury goods imported from China, home to the most advanced techniques, were touted as “karamono (Chinese objects),” these simple tea bowls, made in Korea as everyday utensils, were viewed in Japan as luxury items. The term“Koryo tea bowls” is used because Korea was also referred to as “Koryo” at the time. Therefore, the name refers to tea bowls made during the Richo Dynasty, and not to “tea bowls from the Koryo Dynasty.”

While being beloved among select groups of aesthetes, crafts from the Richo Dynasty were long disregarded by the general public. This changed thanks to Yanagi Soetsu, a Japanese philosopher and the founder of the Mingei Movement. Active in Japan in the late 1920s and 1930s, Yanagi insisted on showcasing the beauty of Korean handicrafts. He was first exposed to these traditions in 1914, when he received a Richo Dynasty chamfering pot as a souvenir from Noritaka Asakawa, his friend who was visiting from Korea, and was deeply moved by its simple beauty. Noritaka Asakawa’s brother Takumi, a forestry technician who had travelled to Keijo (modern-day Seoul) the previous year, was also known as a passionate collector and researcher of Korean handicrafts and ancient ceramics. At a time when Korea was being colonized by Japan and its ethnic culture was regarded as inferior, the Asakawa brothers saw Korean crafts disappearing before their eyes and established the “National Folk Museum of Korea” in Keijo in 1924, in order to protect and pass down these cultures. Yanagi was very critical of efforts by the Japanese government to force the people of Korea to assimilate, and was forthcoming with his sympathy and support for Korea’s independence movement.

“Yanagi Soetsu and the Asakawa brothers are heroes to me. In those days, they fought for Koreans using their words. It must have been very difficult for them, as if they were putting their lives on the line,” says Jeong Yonghee, owner of Korean cafe “Lisei” located in Demachiyanagi, Kyoto. Jeong’s father, Jeong Jo-mun, was born in Korea in 1918 and moved to Japan with his parents during his early childhood. He graduated elementary school while working parttime, and after World War II, he managed a restaurant while collecting Korean antiques. In 1988, he founded The Koryo Museum of Art in Kita-ku, Kyoto. As a first-generation ethnic Korean living in Japan, he put a great deal of work into investigating and researching Korean antiques, in an effort to spread understanding of his home country’s culture through works of art.

It has been twenty years since Jeong opened “Lisei” as a space to teach people about Korean craftwork and food cultures. “I myself am not a researcher of Korean art, so it may be coming from the point of view of an amateur, but I do consider myself an enthusiast. I was asked to take care of antiques like this from a young age. They were a part of my life growing up.” It was the existence of a store run by a Japanese owner that initially motivated her to open this cafe.

“About thirty years ago, I visited a coffee shop named “Sabo Rihaku” in Jimbo-cho, Tokyo [relocated to Kyodo in 2004, closed in 2014]. The owner was also an enthusiast of crafts from the Richo Dynasty.When I stepped inside, I was shocked. He was such a passionate collector that he even carefully preserved wastepaper from the Richo Dynasty. He told me that he was envious that I was born from an ethnic group that created such beautiful items, and that his dream was to spend his last days in a traditional Korean mud and straw roof house. I felt a kind of culture shock meeting this Japanese man who had such strong feelings towards Korean arts and crafts. My desire to understand their allure motivated me to open my own store. After being face to face with crafts from that era for all these years, I’ve just started to see a glimpse of what makes them so special.”

The variety of ceramics and furniture from the Richo Dynasty – a large white porcelain vase, painted Mishimade tea bowl (Buncheong ware), Ban Daji and Tag Ja (tables),and much more – found in all corners of the café were not items Jeong inherited from her father. “I purchased everything on monthly installments, one by one. I collected all of it myself.” Most of the crafts from the Richo Dynasty don’t have complex designs or flashy decorations and are solidly built, utilizing the natural textures of the raw materials. Jeong continues to be exposed to their inner beauty through her daily life. “Today, crafts from the Richo Dynasty are considered to be luxury items, but they were originally everyday articles that were regarded as folk art and not as something flashy. The terrain in Korea is primarily bedrock, and during ancient times, wood was considered a valuable natural resource, so even crooked trees were used as they were. To make the most out of the materials, the furniture was made according to the shape of the wood, so each item features a unique size and shape and no two are perfectly alike. The finish is not perfect, but that’s what makes it charming. In Japan, there is an aesthetic sense known as “wabi-sabi” (emphasizing quiet simplicity), but this point of view can be found in the cultures of other countries as well. This quality can be found anywhere.”

The culture that Jeong has continued to convey through her cafe, “Lisei,” was born from the everyday lives of common people in Korea. Inextricable from that culture is the presence of food. In particular, the traditional tea made from herbal medicine believed to have curative effects was an important part of everyday life in Korea, and this culture has been passed down to the present day.

“Common people couldn’t afford to drink green tea, so instead they spent the time between their grueling fieldwork making their own kind of tea, by grinding tree roots and leaves, soaking pine nut seeds, Chinese wolfberry fruit and jujubes and adding honey to make it easier to drink. This drink soon became a staple, and was once popular as a nourishing “alternative tea.” Japanese people may not be familiar with this aspect of Korean food culture, but consider how not so very long ago, no one in Japan ate kimchi, but today you see it everywhere, and everybody loves it. I believe that cultural exchange begins the moment you taste something and think that it’s delicious. All it takes is trying something new.”

The year before last, Jeong opened her second store, “Teramachi Lisei,” which specializes in traditional Korean tea and sweets. The interior of the store was decorated with Jeong’s unique sense of design: a blend of Japanese and Western crafts along with crafts from the Richo Dynasty. Behind it all is the history of countless people exploring cultures, including arts and crafts, and connecting with one another through cultural preservation. “No matter how small an ethnic community might be, its people hold a sense of pride in their culture. I myself have received discrimination as a Korean national living in Japan and have wondered why I wasn’t born where my parents were born, but now I feel that I was very lucky to have been born here. It has allowed me to understand two different cultures. I can now see that my father was correct in not making the easy choice to be naturalized as a Japanese citizen in order to eliminate tensions. Japan and Korea are neighbors. Almost like brothers. We have a history of sharing cultures. It would be great if one day we could become friendly with each other. I don’t plan on keeping this store open forever, but I want to keep it going as long as I can. I believe that this is my destiny in life.” (Reprinted from Subsequence vol. 1)

Eclectic

HOLDING BACK THE YEARS Hiroki Nakamura and the Restoration of Richard Neutra’s “Schaarmann House”

2025.02.21

Eclectic

Media: &Premium December Issue

2024.11.12

Eclectic

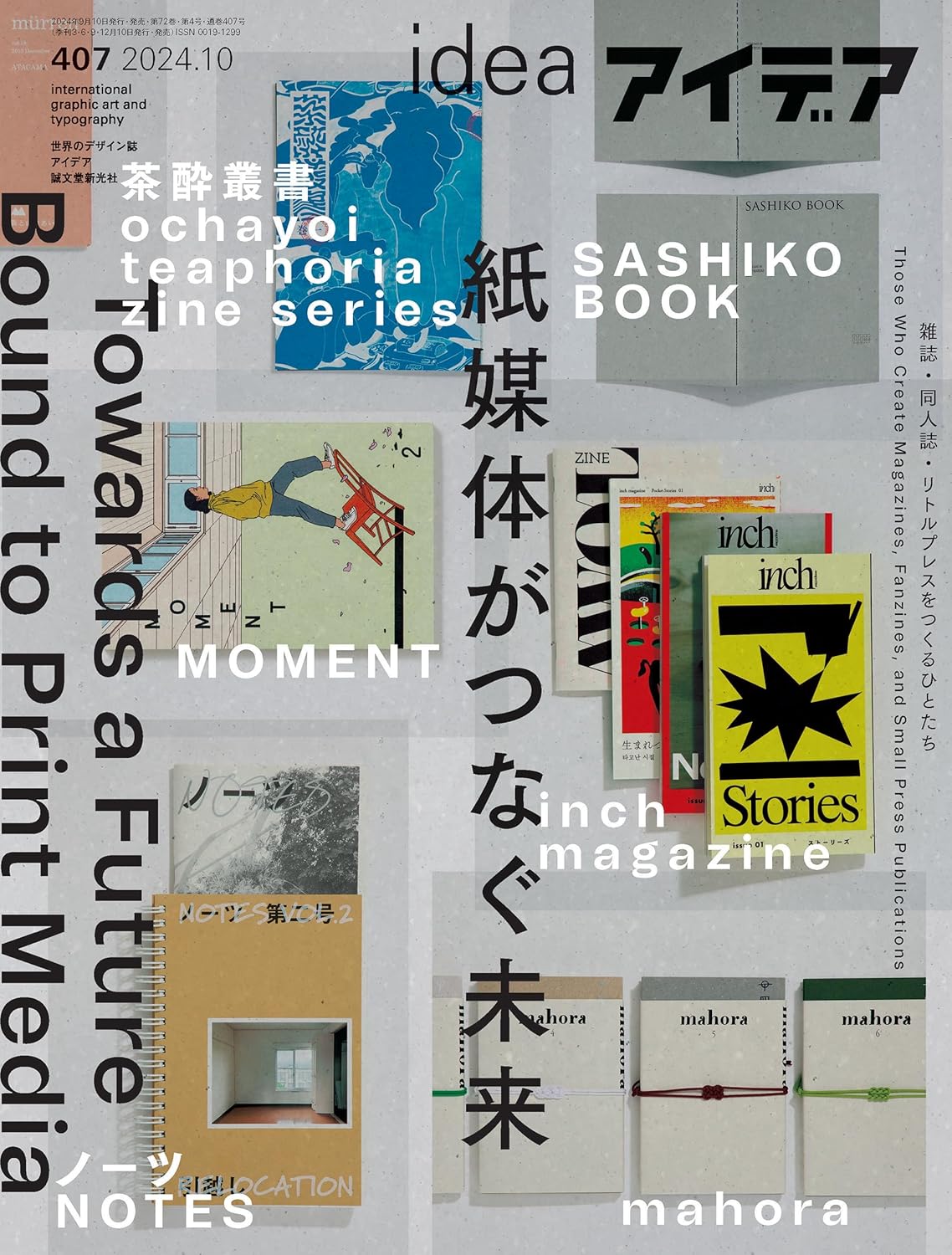

Notice about a special feature / IDEA Magazine No. 407

2024.09.10

Eclectic

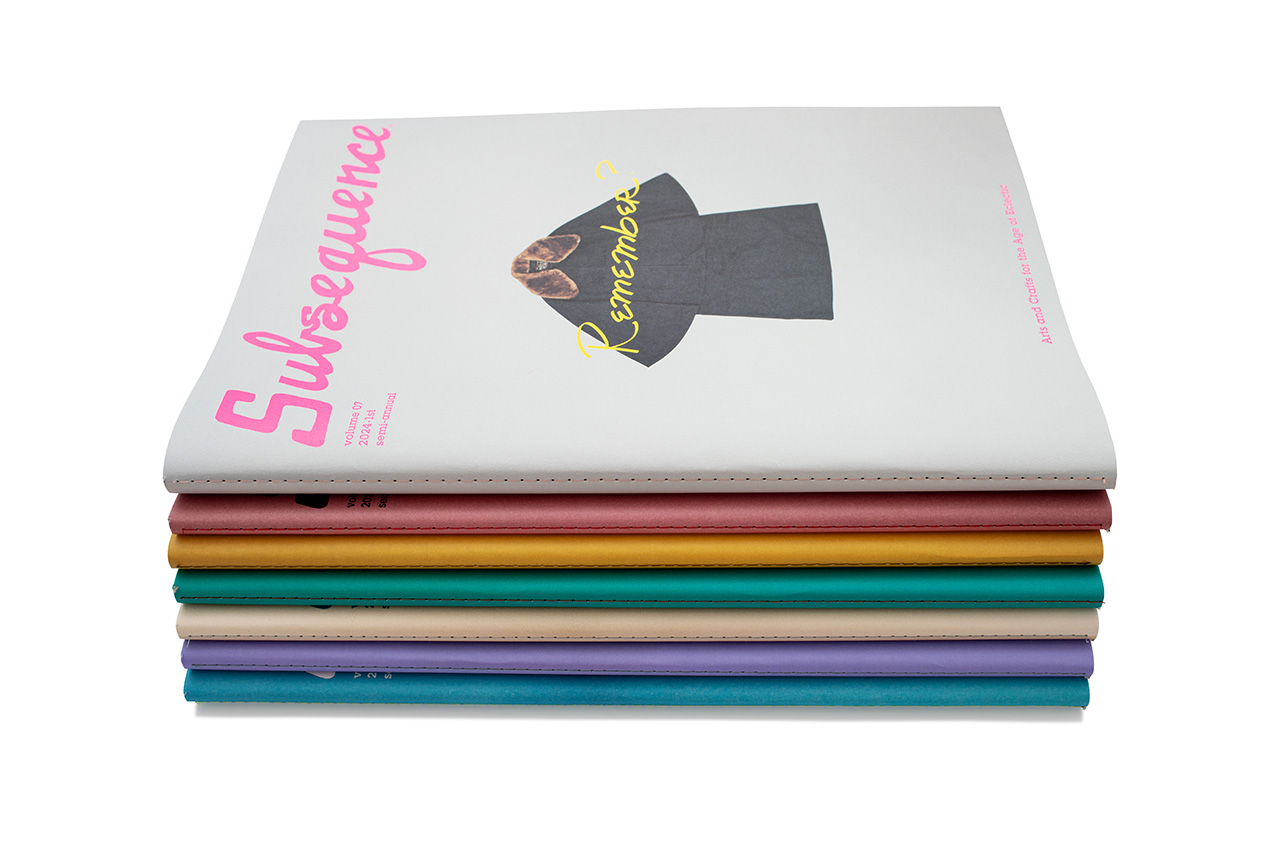

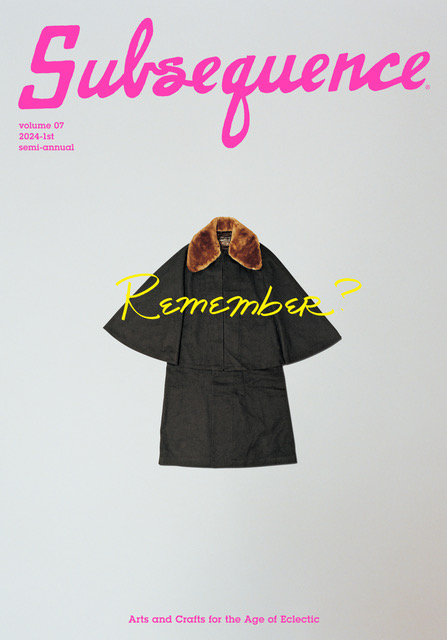

vol.7 / Natural Dyed Thread

2024.08.26